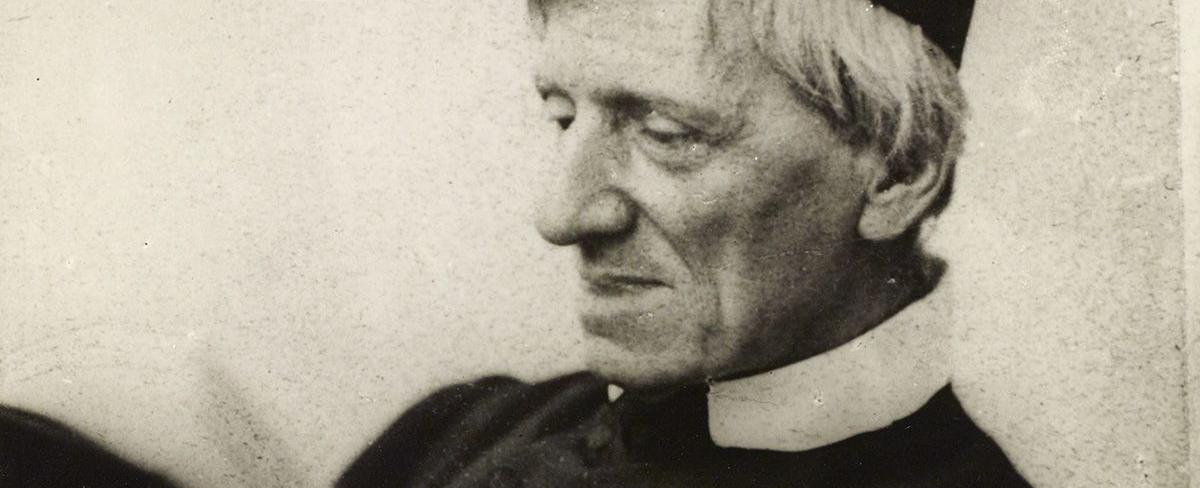

John Henry Newman’s Pneumatological Hermeneutics and Dei Verbum

The hermeneutical landscape of modernity has been profoundly influenced by Enlightenment rationalism, historical criticism, and the fragmentation of religious authority, all of which pose significant challenges to the faithful interpretation of Sacred Scripture. In the nineteenth century, these tensions were acutely felt in religious controversies, such as the Protestant emphasis on sola scriptura, which often privileged individual interpretation over ecclesial tradition, and emerging Catholic debates over historical-critical methods, as exemplified by figures like Alfred Loisy and the Modernist Crisis. John Henry Newman navigated similar turbulent waters as an Anglican convert to Catholicism, developed an implicit pneumatological hermeneutics that positioned the Holy Spirit as the vital guide for both personal and communal engagement with the biblical text. This approach not only harmonized reason with faith but also underscored the Spirit’s illuminating presence, which enabled authentic assent and doctrinal continuity amid historical change.

Newman’s historical context, marked by the Oxford Movement’s resistance to Protestant individualism and his own grappling with Catholic ultramontanism, shaped his conviction that scriptural interpretation requires divine assistance to transcend mere human analysis. While Newman’s contributions of doctrinal development, conscience, and ecclesial authority have dominated scholarship, his pneumatological hermeneutics—i.e., the Spirit’s role in animating interpretation—remains underexplored, as is noted by scholars like Ian Ker and Nicholas Lash.1 This article argues that Newman’s understanding of the Holy Spirit as the guiding agent in ecclesial and personal scriptural interpretation offers an underexplored bridge between patristic hermeneutical traditions and Vatican II’s Dei Verbum §12. By illuminating how the Spirit informs conscience, assent, and ecclesial reception, Newman’s thought provides a distinctive theological insight that resonates with the council’s call to interpret Scripture “in the same Spirit in which it was written.”2 This perspective focused on doctrine or epistemology represents a fresh contribution and highlights Newman’s enduring relevance for contemporary hermeneutics.

Positioned within broader Newman scholarship, this study builds on Avery Dulles’s ecclesiological analyses and Matthew Levering’s participatory theology, while extending them to emphasize the pneumatological dimension.3 It also engages recent works, such as Donald Graham’s exploration of Newman’s pneumatic ecclesiology, to underscore how his Spirit-centered approach anticipates Vatican II's ressourcement theology.4 Through this framework, the paper reveals Newman's pneumatology as a crucial resource for navigating modern interpretive challenges, affirming the Spirit’s active role in the Church’s ongoing life.

Newman’s Pneumatology of Interpretation

Newman's pneumatological hermeneutics is not a systematic treatise; rather, it is an implicit thread woven throughout his writings, which emerges organically from his reflections on faith, reason, and the Church. This subtlety reflects his aversion to abstract speculation, favoring instead an experiential theology grounded in the Spirit’s quiet operation within the believer and the community.

In An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845), Newman portrays doctrinal growth as Spirit-guided and faithful to revelation. Development, he says, proceeds through “the spontaneous process which goes on within the mind itself,”5 and because the Church is catholic in time and place, “principles require a very various application according as persons and circumstances vary.”6 Under this providence, Newman can even quote Tertullian to describe the Paraclete’s work, whereby “discipline is directed, Scriptures opened, intellect reformed, [and] improvements effected.”7 Read through this pneumatological lens, doctrinal unfolding resists a merely rationalist hermeneutic by insisting that the Spirit discloses Scripture’s implications in history. As Newman puts it elsewhere, the Spirit is “the secret Presence of God within the Creation: a source of life amid the chaos, bringing out into form and order what was at first shapeless and void.”8

Newman’s An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent (1870) further clarifies this pneumatological dynamic of interpretation through his account of the illative sense, an intuitive faculty animated by the Spirit, who helps lead the Christian to real assent. Newman describes conscience as “a messenger from Him who ... speaks to us behind a veil,” where the Spirit enables existential engagement with Scripture beyond mere notional knowledge.9 Newman elaborates: “The Holy Spirit ... takes possession of us, and claims our thoughts, desires, and affections for God.”10 This personal dimension highlights hermeneutics as spiritual transformation.

Newman’s Parochial and Plain Sermons (1834–1843) provide vivid examples of this implicit pneumatology. In his sermon titled, “The Indwelling Spirit,” Newman depicts the Spirit as the “interior teacher” who “enlightens the mind” to perceive scriptural depths, stating: “He pervades us … as light pervades a building, or as a sweet perfume the folds of some honourable robe; so that, in Scripture language, we are said to be in Him, and He in us.”11 Similarly, in “The Gift of the Spirit,” Newman emphasizes the Spirit’s guidance in interpreting Scripture amid personal trials: “He it is who enables us to read the Scriptures aright and who makes ‘the word of Christ’ dwell richly in us.”12 These sermons reveal the Spirit’s role in fostering a devotional hermeneutic, bridging intellectual assent and lived faith.

In On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine (1859), Newman extends this pneumatological account of interpretation to the ecclesial sphere, arguing that the Spirit animates the sensus fidelium, which allows the laity to contribute to scriptural interpretation. Citing the Arian crisis, he notes how the faithful, under the Spirit’s influence, preserved orthodox readings: “the divine tradition committed to the infallible Church was proclaimed and maintained far more by the faithful than by the Episcopate.”13 Newman's patristic engagements reinforce this unity of personal and communal hermeneutics under the Spirit’s direction.

Thus, Newman’s implicit pneumatology positions the Spirit as the hermeneutical fulcrum, integrating subjective experience with objective tradition, and offering a robust framework that prefigures modern theological emphases.

Patristic Foundations

Newman’s pneumatological hermeneutics draws deeply from patristic sources, adapting their insights to counter modern rationalism. His engagements with Augustine, Athanasius, and Origen, among others, form the bedrock of his Spirit-centered approach to Scripture.

Augustine’s notion of the Spirit as magister interior profoundly shaped Newman. In De Magistro, Augustine posits that true understanding arises from the Spirit’s inner illumination, not external signs alone.14 Newman echoes this in his emphasis on conscience as the Spirit’s voice, enabling personal discernment of Scripture. As Augustine writes in Confessions, the Spirit “teaches us from within,” which draws the soul to Christ—a theme Newman retrieves to emphasize interpretation as divine pedagogy.15 This inheritance allows Newman to portray the Spirit as transforming the interpreter, countering Enlightenment individualism.

Athanasius’s anti-Arian pneumatology, which defends the Spirit’s divinity in Letters to Serapion, influenced Newman’s Christological readings of Scripture. Athanasius argues that the Spirit safeguards orthodoxy and thus enables Trinitarian exegesis: “The Spirit is the image of the Son ... who seals us unto God.”16 As translator and defender of Athanasius—evident in his Select Treatises of St. Athanasius (1881)—Newman adopts this to affirm the Spirit’s vivification of Scripture as a witness to Christ.17 He highlights Athanasius's typological method, where the Spirit reveals Old Testament fulfillments in the New, integrating biblical narratives with doctrinal continuity.

Origen, as a precursor in Spirit-guided exegesis, adds another layer. In On First Principles, Origen advocates allegorical interpretation under the Spirit's inspiration, viewing Scripture as having body, soul, and spirit: “The Holy Spirit ... inspires the spiritual sense.”18 Though Newman critiqued Origen’s speculative excesses in Arians of the Fourth Century, he appreciated his emphasis on the Spirit’s role in unveiling deeper meanings, adapting it to stress disciplined, ecclesial hermeneutics.19 This patristic triad—Augustine’s interiority, Athanasius’s orthodoxy, Origen’s allegory—equips Newman to bridge ancient wisdom with contemporary needs, portraying the Spirit as the enduring guide.

Dei Verbum §12

Vatican II's Dei Verbum (1965) marks a watershed in Catholic hermeneutics, with §12 mandating that “Sacred Scripture must be read and interpreted in the light of the same Spirit by whom it was written” (eodem Spiritu quo scriptum est).20 This phrase, echoing patristic sources like Augustine’s emphasis on spiritual illumination, emerged through a complex redaction process influenced by ressourcement theologians.

Preconciliar drafts, initially scholastic and defensive against modernism, underwent significant revisions. The 1960 schema De Fontibus Revelationis prioritized tradition over Scripture, but critiques from figures like Yves Congar and Henri de Lubac prompted a shift toward biblical and patristic integration.21 Congar, drawing on pneumatic ecclesiology, advocated for the Spirit’s unifying role in revelation, while de Lubac emphasized scriptural senses informed by the Spirit.22 Their influence transformed the text, departing from rationalist models toward a dynamic, Spirit-led approach that subordinates historical-critical methods to ecclesial tradition and magisterial judgment.

In context, §12 integrates literary, historical, and theological dimensions while affirming the Spirit’s guidance in inspiration and reception. This pneumatological turn, rooted in patristic echoes—such as Athanasius’s Spirit-sealed exegesis—counters historicism by viewing revelation as a Trinitarian event, where the Spirit actualizes the Word in the Church’s life.23

Convergences and Tensions

Newman’s pneumatological hermeneutics converges with Dei Verbum §12 in their mutual reliance on the Spirit to bridge scriptural inspiration and contemporary reception. Both envision the Spirit as ensuring interpretive continuity, with Newman’s illative sense paralleling the Council’s discernment, and his sensus fidelium aligning with communal exegesis.24 Scholars like Juan Alfaro note Newman’s indirect influence via Congar, who incorporated developmental themes.25

Tensions surface in the balance between personal conscience and ecclesial authority. In his Anglican period, Newman emphasized individual conscience as the Spirit’s voice, critiquing rationalist excesses in tracts like “On the Introduction of Rationalistic Principles into Religion,” where he contrasts the “catholic spirit” with rationalism.26 Post-conversion, his Catholic writings, such as the Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, integrate conscience with magisterial authority, calling it “the aboriginal vicar of Christ” yet subordinate to the Church.27 This evolution highlights a shift from personalism to ecclesial emphasis, potentially mitigating subjectivism in Dei Verbum’s framework. These differences, however, enrich theological dialogue, as Newman's nuance complements the Council's communal focus.

Contemporary Significance

Newman’s pneumatological hermeneutics offer a systematic threefold contribution to contemporary theology—in biblical hermeneutics, ecclesiology, and ecumenism—particularly in light of recent ressourcement scholarship and developments in Newman studies. Newman’s recent elevation to Doctor of the Church has amplified his relevance and positioned his Spirit-centered insights as authoritative for the universal Church and invigorating discussions on revelation and interpretation. This new doctoral status underscores the timeliness of exploring his pneumatology, as it aligns with ongoing efforts to integrate patristic wisdom into modern theological challenges.

In the realm of biblical hermeneutics, Newman’s emphasis on the Spirit as the interior guide counters the dominance of secular, text-critical methodologies by advocating a participatory, Spirit-led approach to Scripture. Matthew Levering’s work on the divine economy echoes this when he argues that interpretation involves a sacramental encounter where the Spirit enables believers to partake in divine mysteries.28 Biblical theologians, such as Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI), have built on similar themes, integrating historical criticism with pneumatic illumination to foster a “hermeneutic of faith” that resonates with Newman’s illative sense.29

Ecclesiologically, Newman’s pneumatological account of the sensus fidelium—a Spirit-given connatural “way of knowing” within the People of God—has fresh traction for synodality and the Church’s common discernment.30 Andrew Meszaros has shown in detail how Congar received and deployed Newman’s insights (especially in Dei Verbum §8), thereby integrating the faithful’s sensus with episcopal discernment in a non-rivalrous, pneumatological key.31 Read alongside Meszaros’s monograph on Newman and Congar, this yields a constructive framework in which the Spirit unites hierarchy and laity without collapsing magisterial responsibility, precisely the balance envisioned by Vatican II and presupposed by contemporary synodal practice.32 Recent magisterial teaching on the sensus fidei and on synodality clarifies the same point: the consensus of the faithful functions as a real theological criterion, yet always in reciprocity with the discernment of pastors and under the guidance of the Holy Spirit.33

In ecumenism, Newman’s developmental hermeneutics, facilitates dialogue across Christian traditions by highlighting the Spirit’s unifying work in scriptural reception.34 Joseph Ratzinger’s ecumenical engagements often invoke Newman to bridge Catholic and Protestant views on authority and revelation, portraying doctrinal development as a Spirit-led process that transcends historical divisions.35 Recent scholarship—including work disseminated by the National Institute for Newman Studies—links Newman’s thought to Vatican II’s ecumenical impulses, especially Dei Verbum’s call for shared biblical study.36 Moreover, interdisciplinary connections with philosophers like Jean-Luc Marion, whose notion of “saturated phenomena” illuminates Newman’s account of real assent, and Paul Ricoeur’s hermeneutical arc, which resonates with Newman’s narrative unfolding of doctrine, broaden his ecumenical appeal (including conversations beyond Christian borders).37 In a polarized world, Newman’s pneumatology underwrites a hermeneutic of charity, where the Spirit fosters unity amid diversity.38

Overall, these contributions, bolstered by the recent declaration of Newman as Doctor of the Church, affirm his pneumatological hermeneutics as indispensable for theological renewal and address contemporary crises in faith, authority, and dialogue.

Conclusion

This study reaffirms the originality of Newman's pneumatological hermeneutics as an underexplored bridge between patristic traditions and Dei Verbum §12, proposing it as a vital, yet underappreciated, resource for theological reflection in the Church today. By foregrounding the Spirit's role in guiding both personal conscience and ecclesial community toward authentic scriptural interpretation, Newman's thought not only anticipates Vatican II's ressourcement but also offers a distinctive lens that enriches ongoing scholarly discourse. The recent declaration of Newman as a Doctor of the Church on November 1st, by Pope Leo XIV further elevates this perspective, inviting theologians to revisit his works with fresh eyes and integrate his pneumatic insights into magisterial teaching.

To sharpen this, future research could pursue several concrete avenues. First, while Andrew Meszaros has mapped the Newman–Congar nexus on development, a fresh comparative study could extend his account by correlating Newman’s illative sense with Congar’s theology of tradition and charisms, testing their convergence against recent synodal processes and global case studies.39 Second, exploring Newman’s implications for synodality—particularly how his sensus fidelium informs Spirit-led decision-making in contemporary synods—should proceed in dialogue with Shaun Blanchard’s account of a “fully Catholic synodality,” which reads Newman’s “consulting the faithful” alongside Vatican II’s reception.40 Third, investigating the Spirit’s place in digital hermeneutics through Newman’s lens might examine how online biblical engagement can be guided by pneumatic discernment, countering the fragmentation of virtual communities and fostering authentic encounters with Scripture. These directions not only extend Newman’s legacy but also demonstrate its adaptability to emerging theological frontiers, ensuring his voice continues to resonate in the Church’s mission.

1 Ian Ker, John Henry Newman: A Biography (Oxford University Press, 1988), 456–78; Nicholas Lash, Newman on Development (Sheed and Ward, 1975), 134–56.

2 Vatican Council II, Dei Verbum, §12, in The Documents of Vatican II, ed. Walter M. Abbott (Guild Press, 1966), 120.

3 Avery Dulles, Newman (Continuum, 2002), 89–102; Matthew Levering, Engaging the Doctrine of Revelation (Baker Academic, 2014), 210–25.

4 Donald Graham, From Eastertide to Ecclesia: John Henry Newman, the Holy Spirit and the Church (Marquette University Press, 2011), 45–67.

5 Newman, Duke (Burns, Oates, & Co., 1870), 248.

6 Newman, SD, 175.

7 Newman, PS (Longmans, Green, 1908), 2:222.

8 Augustine, De Magistro, 14.46, trans. Peter King (Hackett, 1995), 45.

9 Augustine, Confessions, 10.8, trans. Henry Chadwick (Oxford University Press, 1991), 187.

10 Athanasius, Letters to Serapion, 1.28, trans. C. R. B. Shapland (Epworth Press, 1951), 134.

11 Newman, Ath (Longmans, Green, 1895), 1:45–67.

12 Origen, On First Principles, 4.2.4, trans. G. W. Butterworth (Peter Smith, 1973), 275.

13 Newman, Ari (Rivington, 1833), 120–45.

14 Vatican Council II, Dei Verbum, §12.

15 Joseph A. Komonchak, “The Redaction of Dei Verbum,” in History of Vatican II, ed. Giuseppe Alberigo (Orbis, 2000), 3:220–45.

16 Yves Congar, The Meaning of Tradition, trans. A. N. Woodrow (Ignatius, 2004), 56–78; Henri de Lubac, Scripture in the Tradition, trans. Luke O'Neill (Crossroad, 2000), 150–70.

17 Athanasius, Letters to Serapion, 1.19.

18 Dulles, Newman, 95.

19 Juan Alfaro, "The Dual Concept of Tradition," in Vatican II: Assessment and Perspectives, ed. René Latourelle (Paulist, 1988), 110–29.

20 Newman, “Tract 73,” in Tracts (Rivington, 1840), 5:1–10.

21 Newman, Duke (London: Pickering, 1875), 240.

22 Levering, Engaging the Doctrine of Revelation, 220.

23 Joseph Ratzinger, Introduction to Christianity, trans. J. R. Foster (Ignatius, 2004), 189–204.

24 Newman, Dev (1845 ed.), ch. V (“Genuine Developments Contrasted with Corruptions”), §2.

25 Newman, Dev, ch. II (“On the Antecedent Argument in behalf of Developments in Christian Doctrine”), §3.

26 Newman, Dev, ch. VIII (“Application of the Third Note—Its Assimilative Power”), citing Tertullian: “discipline is directed, Scriptures opened, intellect reformed, improvements effected.”

27 Newman, “The Indwelling Spirit,” in PS, vol. 2, sermon 19, “He has ever been the secret Presence of God within the Creation: a source of life amid the chaos.”

28 Newman, PS, 2:266.

29Newman, “On Consulting the Faithful in Matters of Doctrine,” The Rambler (July 1859): 198–230.

30 Andrew Meszaros, “Haec Traditio proficit: Congar’s Reception of Newman in Dei Verbum §8,” New Blackfriars 92 (2011): 231–48.

31 Meszaros, “Haec Traditio proficit,” 231–48.

32 Andrew Meszaros, The Prophetic Church: History and Doctrinal Development in John Henry Newman and Yves Congar (Oxford University Press, 2016).

33 International Theological Commission, Sensus fidei in the Life of the Church (ITC, 2014); International Theological Commission, Synodality in the Life and Mission of the Church (ITC, 2018); General Secretariat of the Synod, Final Document (Vatican City, 24 October 2024).

34 Emery de Gaál and Matthew Levering, eds., John Henry Newman and Joseph Ratzinger: A Theological Encounter (The Catholic University of America Press, 2025)

35 Joseph Ratzinger, “Presentation on the 1st Centenary of the Death of Cardinal John Henry Newman” (28 April 1990), para. 3–4 (on development and conscience as Newman’s “decisive contribution”). See also David G. Bonagura Jr., “The Relation of Revelation and Tradition in the Theology of John Henry Newman and Joseph Ratzinger,” New Blackfriars 101, no. 1091 (2024): 3–18.

36 “Scripture, the Fathers and Ecumenism,” National Institute for Newman Studies; Kenneth Parker, “Saint John Henry Newman, Development of Doctrine, and Sensus fidelium: His Enduring Legacy in Roman Catholic Theological Discourse,” Journal of Moral Theology (2021), PDF. For Newman’s specific influence on Dei Verbum, see J. R. Vélez-Giraldo, “Newman’s Influence on Vatican II’s Constitution Dei Verbum,” Scripta Theologica 51, no. 2 (2019): 469–91.

37 Jean-Luc Marion, “The Theory of Saturated Phenomena,” in Being Given: Toward a Phenomenology of Givenness, trans. Jeffrey L. Kosky (Fordham University Press, 2002); Newman, GA (Burns, Oates, 1870); Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, vol. 1, trans. Kathleen McLaughlin and David Pellauer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984). For an accessible précis on the “saturated phenomenon,” see the Fordham chapter abstract.

38 Tracey Rowland et al., in de Gaál and Levering, John Henry Newman and Joseph Ratzinger, esp. essays on revelation, conscience, and ecclesial unity; and “Newman, the Guide of Conscience for Ratzinger,” The Newman Review (29 November 2023).

39 Andrew Meszaros, The Prophetic Church: History and Doctrinal Development in John Henry Newman and Yves Congar (Oxford University Press, 2016).

40 Shaun Blanchard, “Consulting the Faithful: John Henry Newman’s Relevance for a Fully Catholic Synodality,” Spiritan Horizons 19 (2022): 98–113.

Share

Marvin Jhan Santos

Marvin Jhan Santos holds a MA in Theology and MA in Philosophy, and is currently pursuing a PhD in Theology. His research focuses on liturgical theology, sacramental ontology, and medieval religious orders, and is a current faculty of Theology at Don Bosco Cristo Rey High School in Washington, DC.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS