Why Lingard Didn't Like Newman

“Tibi soli” (for your ears only) began an 1848 letter of John Lingard to his friend Robert Tate. It was for Tate’s ears only because it was “a gossiping letter written without consideration.” The letter was certainly gossipy, but it was also an informative, if grouchy, summation of old Fr. Lingard’s suspicions regarding much of what came to characterize the “Second Spring” revival with which he closely associated the famous convert John Henry Newman.

"I am told that Dr Wiseman [Nicholas Wiseman, soon to be Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster] is giving a retreat at Ushaw. I am sorry. He will give it in the Roman that is, the Jesuit manner. I think the old Douai manner much better. This new fashion of doing it appears to me an invention to excite fanaticism. At least such was the method of Gentili & Furling, who I believe turned the heads of half the catholic females, and brought about something very like the fanatical revivals in Italy. I shall not be surprised, if some or other of your most promising subjects be induced to leave you for the Oratorians or the Newmanites, or thisites or thosites with which we now abound."[1]

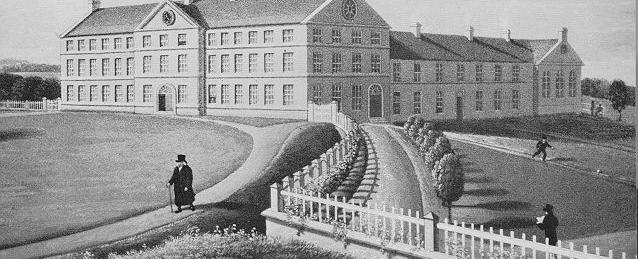

This flippant letter, which Lingard knew was a bit fussy (he closed self-reflectively: “excuse me for troubling you with my nonsense”), nevertheless not only put its finger on a number of neuralgic fault lines in the English Catholic community at mid-century, it also harkened back to several age-old disputes that were as yet unresolved. These disputes were trending in a direction that disturbed men like Lingard, one of the few remaining paragons of “old” English Catholicism. In the short passage quoted above, Lingard registered his distrust of the too-Romanized Dr. Wiseman (and equated this romanitas with the Jesuits), while pining for the implicitly more English “manner” of Douai, the seminary across the Channel in which Lingard and many of his priest friends were trained. The “method” of giving spiritual retreats that Lingard associated with Italy was censured for its propensity to ensnare people (women in particular) and lead to “fanaticism,” the great bogeyman of the enlightened and patriotic “Cisalpine” Catholicism of the late eighteenth century.[2] Finally, the age-old tension between secular (diocesan) clergy and “regulars” (members of religious orders) lurked in the background.[3] It was in that context that Lingard explicitly evoked Newman. By 1848, Newman was both an inspiration and a source of controversy in the English Catholic community. Lingard remarked upon Newman’s career several times in his correspondence, usually with a mixture of suspicion and curiosity.

The historian Fr. John Lingard (1771–1851) was probably the most important English Catholic intellectual of the first half of the nineteenth century. John Henry Newman (1801–1890) was certainly the most important of the second half of that century, and probably the greatest post-Reformation English-speaking Catholic theologian. Lingard and Newman had a great deal in common. Both were men of vast learning and deep love for the church who merged serious scholarly engagement with wide-ranging pastoral commitments. Lingard, who spent most of his life as a parish priest in the north in Lancashire, and Newman, the Oxford don-turned-cardinal, were both at the center of the theological and ecclesio-political debates that shaped English Catholicism in the nineteenth century. Lingard and Newman had sincerely respectful stances towards the papacy, and yet looked askance at the excesses of the burgeoning ultramontane movement. And both men fought—in different ways and in different contexts—to protect and defend the Catholic community from the bigotry and prejudice that was so deeply rooted in English society. In light of these numerous affinities, the many negative (sometimes downright rude) statements about Newman and his associates in Lingard’s correspondence can be somewhat jarring to come across. How could Lingard—a kind and likeable priest-scholar who earnestly desired and labored for conversions to Catholicism—possibly have disliked the man who was perhaps the most celebrated English convert of all time? The answer to this question reveals more about Lingard than about Newman, and also sheds light on the state of the English Catholic community in the years spanning the growing reputation of Newman (1830s and 40s) up to Lingard’s death in 1851.

Lingard’s Suspicion of the Oxford Movement

At first glance it seems deeply contradictory that a man like Lingard, who dreamed of England’s return to the Catholic fold, would be suspicious rather than celebratory in the wake of the wave of Anglican converts created by the Oxford Movement. Derogatory references to “Puseyites” and “Newmanites” dot Lingard’s correspondence from the late 1830s through the 1840s. In 1845, the year of Newman’s conversion, Lingard seemed guardedly optimistic about Newman’s personal potential, but was also realistic (or perhaps pessimistic) about the practical challenges arising from the conversion of Anglican clergy:

"I am glad that Mr. Newman’s work is coming out [the Essay on Development].[4] When he has published it, he must be set to something else. These converts must be employed. Had he a small establishment somewhere, as he had at Littlemore, he might bring over more, and have something to occupy his zeal. Otherwise he will be of little use to us, and the excitement caused by his conversion will die away."[5]

While this statement appears somewhat cold, as an “old” Catholic Lingard was a firm believer in the irenic strategy that predominated during his formative years in the eighteenth century, when Catholics not only in England but across the English-speaking world advanced strategies to curtail or eliminate the varieties of legal disabilities and cultural prejudices that still loomed large. Still lurking in the background was the ominous possibility of mob violence, not only in Ireland and America but in England as well; Lingard was a boy when the Gordon Riots ripped through London and other cities in 1780. In light of this, Lingard not unreasonably feared that converts, aflame with zeal for the One True Church, would confirm the worst suspicions of their Protestant neighbors through triumphalist polemics or the “foreign” religious tastes and styles that went along with them. For prudential and for theological reasons, old English Catholics like Lingard had done much to play down or even eliminate these combative or showy tendencies.[6]

While Lingard might at times seem unnecessarily caustic or even snobbish in his rhetoric, we should keep in mind two things. First, much of our direct evidence of Lingard’s views on Newman, other converts, and the Oxford Movement comes from private correspondence with friends, and not from his numerous published works (though his general proclivities and aversions can be easily gleaned from his published corpus). Second, Newman and the many converts of this era only knew life as Catholics after the vaunted Catholic Emancipation Act finally passed parliament in 1829. They had not experienced, as Lingard had, the anxieties of life before the “Relief Acts” of 1778 and 1791 eliminated most of the old Penal Laws. Lingard knew firsthand the numerous legal and practical disabilities Catholics faced, such as the need to be educated abroad in Europe. Much less had the new converts experienced the terror of Revolutionary armies abroad or “No Popery” mobs at home.

Lingard was very curious about the Oxford Movement and the converts associated with it. His opinion definitively soured sometime between 1839, when he evinced a critical yet nuanced appraisal of the merits of the “Puseyites,”[7] and 1845, when he called them “lunatics”![8] In 1849, the twilight of his life, the aging historian revealed he didn’t fully trust the new converts with such bitter lines as: “I hope someone will snub the self-sufficiency of these English Philipnerists” who bring “with them into the Oratory all the false notions which they had imbibed at Oxford.”[9] He praised his friend John Edward Price for giving the “neo-Oratorians” who had attacked Price in the Rambler “a sly lick or two.”[10] In March 1851, several months before his death, Lingard wished he could “attack” the Newmanites on their “philosophy of romance” [Romanticism]. “I hate their self-sufficiency.”[11]

Lingard followed news of Newman and his conversion closely.[12] However, in addition to never really permitting Newman to shake his association with the Oxford Movement (a strike against him in Lingard’s eyes), the old Cisalpine also seems to have negatively associated Newman with Faber (whom he called “credulous”)[13] and with the burgeoning ultramontanism and Romanticism sweeping English Catholicism. Unfortunately, Lingard never recognized Newman as the profoundly unique thinker he was, nor as one who deftly eschewed the standard binaries and party lines of the age and of the church. Lingard even admitted, in 1845, to not having yet read Newman![14]

In 1848, Lingard, only half-joking, complained to Price (whom he praised for attacking Faber in print) that in the eyes of the “regulars & converts” he was a Gallican and Jansenist.[15] Lingard was, of course, no Jansenist, though like many of his generation he had conciliarist sympathies and tendencies, and was deeply unnerved by the ultramontane excesses he saw on the rise. Underneath the half-joking reference to Jansenism was a very real point: Lingard felt increasingly alienated in the new culture of English Catholicism, where perspectives and attitudes he saw as venerable and tried-as-true were regarded by some ardent new converts as evidence of a dangerous fifth column.

“Enthusiast” Converts Riding “Rough-Shod” Over Old Catholics

“Of late the converts seem to have ridden rough-shod over the old Catholics,” Lingard complained in 1847.[16] Lingard’s sense of alienation from the new English Catholicism of the Second Spring arose for two basic reasons, one emotional and the other principled. The first reason was simply jealously, a sense that the “new” Catholics were gaining the upper hand and had more support in Rome and in much of the wider Catholic world (that sense was undoubtedly correct). Put more sympathetically, Lingard felt that zealous converts (he repeatedly calls them “Newmanites”) did not show proper respect to the “old” Catholics: “[Newmanites] certainly think much of themselves and very contemptuously of all others.”[17] Lingard resented that the new converts seemed to think that they were somehow more Catholic (or more orthodox) than the old, due to their zeal, ultramontanism, and preference for traditional devotions. The “old,” on the other hand, were generally more subdued in their piety, and leaned conciliarist ecclesiologically, or were at least not ultramontane. In Lingard’s case this tension does not seem to have been class-based. Lingard came from a humble background, and he was not an aristocrat’s chaplain, as were many of the leading “Cisalpine” clergy of the generation before him.

Lingard was also clearly jealous of the coziness—such that he perceived it—of Newman and many converts with Rome, Propaganda, and the soon-to-be restored hierarchy. “According to the daily news,” Lingard reported in 1847, “Newman is on his way from Rome, with a cargo of twelve bishoprics[.]”[18] He complained months before his death that he sent a copy of one of his works to Cardinal Wiseman, “but do not think he will be pleased with it, as probably he would prefer a work on the same subject from his friends the Newmanites.”[19] There is a kind of paradox here, or at least a tension, because on one hand Lingard intimated that the new converts were not Catholic enough—or at least suspiciously attached to “false ideas they imbibed at Oxford”—but on the other hand they were resented for being too Catholic, in the sense of trying to assimilate their Catholicism too much to a foreign standard that was Roman, “Jesuitical,” or Italian.

The second reason for Lingard’s sense of alienation from those he called the “Newmanites” was more principled. When he bluntly admitted to John Walker in January of 1850 that he “didn’t like Newman” that reasons he cited are telling: “too much fancy or enthusiasm.”[20] While there is an element of taste here—Lingard was a man of the Catholic Enlightenment who naturally recoiled from Romanticism and Pugin’s neo-Gothic revival—there was also an important principle at stake.[21] For Lingard, and many of his generation, the theologically correct and pragmatically most effective way to engage Protestants was through stripping away superstitions, triumphalism, and any unnecessary accretions to the Old Faith. Protestants rightly resented all of these things. What remained could be grasped by Protestants of good will as the pure faith of their English ancestors and, indeed, of the early church. This line of thought was promoted by prominent English-speaking leaders of the generation before Lingard, like Joseph Berington and the American Archbishop John Carroll. When Catholicism was shorn of this dead freight, and when the embers of prejudice and bigotry in Protestant hearts were extinguished through demonstrations of the goodness, honesty, and patriotism of their Catholic neighbors, the pure truth of Catholicism, rightly understood, will shine through and convert many. So the apologetic strategy went.

To Lingard, a man who was nearing 60 when he experienced the elation of the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829, the new apologists (that he called “Newmanites”) threatened to destroy decades and decades of positive momentum, both in the realm of cultural-political acceptance and in the realm of apologetics and theology. Numerous comments to this effect are sprinkled throughout his correspondence, especially in the late 1840s. In the same letter in which he bluntly stated that he didn’t like Newman, Lingard bemoaned that Protestants were “making much noise and ridicule” about a work “written by one of [the] Newman Converts.”[22] In a letter written in the twilight of his life he ranted about Pugin and wished that “Newmanites” would not be the ones to answer anti-Catholic authors since they risk doing more harm than good.[23] Lingard’s apprehensions cohered with the age-old fears of English Catholics—that their religion would be perceived or represented by anti-Catholic neighbors as superstitious or, even worse, as foreign.

Conclusion: Newman on Lingard

Newman, thankfully, seems to have been totally unaware that Lingard disliked him. At the death of Lingard’s close friend John Walker in 1873 (to whom Lingard confided so much of his disdain for “Newmanites”!). Newman wrote of his “greatest esteem” for Walker. Newman “looked at [Walker] with veneration as one of the few remaining priests who kept up the tradition of Dr. Lingard’s generation of Catholics.”[24] Seven years earlier, Newman had written to John Walker, thanking him for sending information on Lingard’s intra-Catholic controversies in the early 1830’s. In light of his later praise of Lingard, Newman presumably approved of his comportment. In Lingardian fashion, Newman went on in the same letter to caution against the merits of seeking out confrontation with Anglicans.[25] Rather humorously from the vantage point of those aware of Lingard’s rants against “Newmanites,” Newman told William Walker that Ushaw should preserve all the letters Lingard sent to his brother John Walker (thankfully, for this researcher, it seems they did!). Letters, Newman said, are a part of a man, as are his opinions, whatever they are. Newman noted that it was unlikely any “abuses against charity” would be found in Lingard’s correspondence.[26]

Lingard’s manifold complaints about “Newmanite” converts, varied and sometimes unfair though they were, shed important light on the clash of ecclesiastical and intellectual cultures in the English Catholic community at mid-century. As the last lights of the eighteenth-century church of the enlightened Cisalpine gentlemen and their irenic scholar-priests were dying out, the identity of the English church was increasingly shaped by the confident, “enthusiast,” pro-papal, and devotional Catholicism of Manning and Newman, Faber and Ward. This “Second Spring” Catholicism turned out to not in fact be the monolith that grumpy old Lingard perceived it as. Had he lived longer, or had he been fairer to Newman and actually engaged with his thought as an individual rather than a symbol, Lingard would have seen that the sensitive and brilliant Oxford convert was in fact preserving many of the concerns that Lingard himself held dear. We should keep in mind that in the years around Newman’s conversion, Lingard was an old man, suffering on and off from ill health. It is nevertheless unfortunate that Lingard did not engage with Newman’s ecclesiology in particular. He would have discovered a kindred spirit with nuanced and sophisticated views of the structures and offices of the church. Lingard would have also seen how much more he had in common with Newman than with the Mannings, Fabers, and Wards with which he lumped him together.

[1] Lingard to Tate (7 October [1848]), UC/P25/1/T1/123. In addition to the published material (much of it cited here in an introductory sketch on Lingard), this essay draws from the Lingard Papers collection at Ushaw College Library (henceforth UC), the most important archival collection for the study of Lingard. The author hopes to visit some other relevant archival collections in the UK once international travel is again possible. An informative chapter on Lingard from John Vidmar should be included in my review of the secondary literature on Lingard: Vidmar, English Catholic Historians and the English Reformation, 1585–1954 (Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, 2005), 52–74.

[2] Lingard reported on the Ushaw retreat in similar terms to his friend John Walker: “So Dr Wiseman is going to give a retreat at Ushaw. My notion is that the old Ushaw kind of retreat was much better than this Rmano (sic) Jesuitical kind of retreat, which appears to me calculated to engender fanaticism and nonsense. But as I never was present at one I am no judge.” (!) Lingard to Walker (26 September 1848), UC/P25/1/W1/357.

[3] It was apparently insignificant to Lingard that the Congregation of the Oratory is canonically a much different kettle of fish than the Jesuits or the mendicant Friars.

[4] Lingard also expressed interest in the Essay on Development in a letter to Walker (28 November 1845), UC/P25/1/W1/231.

[5] Lingard to Husenbath (18 November 1845), UC/P25/7/156. A concern for putting converts “to good use” arises throughout Lingard’s correspondence. For example, see also Lingard to Tate (1 December 1845), where Lingard urges Tate to “make good use of” Newman and Faber (UC/P25/1/T1/88).

[6] In contrast, Lingard praised the style of the Catholic Magazine, which he was “delighted with … both on account of its fearless but temperate advocacy of Catholic doctrine & practice.” Lingard predicted “protestants will continue to consult it for a full & honest exposition of our feelings & objects.” See Lingard to Price (11 June [1848?]), UC/P25/7/872.

[7] See, for example, Lingard to Walker (4 May 1839), UC/P25/1/W1/28. “I look upon the Oxford tractists as much enemies to us as their opponents—perhaps more so because it is necessary for them to prove their enmity. Yet their tracts will make some persons, who take the trouble to think, less hostile to the ancient church.”

[8] The offending detail was the purported “Puseyite” desire for the Roman breviary to be standard in all Church of England parishes. See Lingard to Walker (4 April 1845), UC/P25/1/W1/202.

[9] Lingard to Tate (17 January 1849), UC/P25/1/T1/128. Lingard believed that all the Cambridge dons were Puseyites. See Lingard to Walker (18 January 1845), UC/P25/1/W1/192.

[10] Lingard to Price (7 November 1849), UC/P25/7/862.

[11] “What will the Newmanite reviewers of Macaulay say to my work? Nothing I suspect. I should like them to find fault. I could then attack them on the philosophy of romance; and their praise of so great an enemy of ours. I hate their self-sufficiency.” Lingard to Walker (6 March 1851), UC/P9/7/9.

[12] See, for example, Lingard to Walker (30 August 1845), UC/P25/1/W1/221 (repeating a rumor that Lingard planned to join the Jesuits); Lingard to Walker (9 September 1845), UC/P25/1/W1/222 (news on possibility of Ward and Newman’s conversions); Lingard to Walker (18 September 184[?5]), UC/P25/1/W1/223 (on Newman’s conversion shaking the “Puseyites”); Lingard to Walker (16 October 1845), UC/P25/1/W1/226 (on Newman’s justification for converting; Lingard rightly predicts Pusey “will not come over”).

[13] Lingard to Price [1849?], UC/P25/7/892.

[14] Lingard to Walker (17 December 1845), UC/P25/1/W1/237. Lingard also admits he couldn’t get through Ward’s work.

[15] Lingard to Price (6 September [1848?]), UC/P25/7/874. “I have no doubt that I am a Gallican & a Jansenist with the regulars & converts. In July, I wrote to inquire after a document at Stonyhurst, but have never received an answer.” Lingard had actually been accused of Jansenism in the past, though for reasons that were manifestly unfair. He leaned into the accusation when joking around with friends: “No wonder that I am a jansenist,” he wrote to Walker in light of a disagreement he had had with a bishop. Lingard to Walker (18 July 1848), UC/P25/1/W1/346.

[16] Lingard to Tate (12 April 1847), UC/P25/1/T1/113.

[17] Lingard to Walker (5 February 1850), UC/P9/7/4.

[18] Lingard to Walker (19 December 1847), UC/P25/1/W1/326. Lingard recognized the possibility this rumor was false (it was), adding “if this be true the Romans are in greater haste than usual.”

[19] Lingard to Walker (4 April 1851), UC/P9/7/67. See also same to same (9 April 1851), UC/P9/7/68. “I sent to the Cardinal a copy of my Observations on the Report. Will he have noticed it in his sermon of last Sunday? I suppose not. He would rather that the subject had fallen into the hands of his Newmanites.”

[20] Lingard to Walker (12 January 1850), UC/P9/7/1.

[21] See, inter alia, Lingard to Walker (6 March 1851), UC/P9/7/9.

[22] Lingard to Walker (6 March 1851), UC/P9/7/9.

[23] Lingard to Walker (14 March 1851), UC Walker Correspondence 1396.

[24] Newman to William Walker (27 June 1873), UC/P 20/162.

[25] Newman to John Walker (12 March 1866), UC/P 20/160.

[26] Newman to William Walker (19 September 1873), UC/P 20/165.

Shaun Blanchard

Senior Research Fellow, NINS, and Associate Editor, NSJ

Shaun Blanchard is Senior Research Fellow at the National Institute for Newman Studies and Associate Editor, NSJ. He is the author of The Synod of Pistoia and Vatican II (OUP, 2020). With Ulrich Lehner, he co-edited The Catholic Enlightenment: A Global Anthology (CUA, 2021), and, with Stephen Bullivant, co-wrote Vatican II: A Very Short Introduction (OUP, 2023). Shaun is currently working on a monograph study of Catholic ecclesiology in the English-speaking world from the Cisalpines to Newman.

QUICK LINKS