Vice-Principal of Oxford’s Botany Bay: Newman at St. Alban Hall

Two hundred years ago, on 26 March 1825, John Henry Newman was appointed vice-principal of St. Alban Hall, Oxford. The position, which he held for a year, meant acting as tutor, chaplain, bursar, and dean of its dozen undergraduates, giving most of the lectures, setting weekly assignments, and dining with the students three times a week.

Newman had been ordained a deacon in the Church of England the previous year and shortly afterwards had started pastoral work as the curate of St. Clement’s, a growing working-class parish on the edge of Oxford. He had thrown himself into parish work, carrying out baptisms, “churchings,”1 weddings, burials, visiting the sick and dying, setting up a Sunday school, undertaking a parish visitation—in which he called on around 400 homes in a five-week period—as well as setting himself the ambitious goal of preaching twice a week. He combined all this with his fellowship at Oriel College (1822–1845) and his academic projects.

Richard Whately

The year before becoming vice-principal, Newman had finished an article on Cicero commissioned for the Encyclopaedia Metropolitana, and during his year at St. Alban Hall he had begun two others for the Encyclopaedia, one on the philosopher Apollonius of Tyana and a sequel on miracles. These commissions came to him via Richard Whately, the Oriel Fellow who had been asked to take care of Newman on his arrival at the college in April 1822. That summer, Whately had engaged Newman to help him write his textbook Elements of Logic, which first appeared in the Encyclopaedia Metropolitana (1826). Newman’s task was to construct a rough draft of the article after transcribing various manuscripts of Whately on logic, which were to form the basis of the work.2 Elements of Logic (1827) became the standard work on logic in Oxford until it was superseded by John Stuart Mill’s System of Logic (1843).

Richard Whately was appointed principal of St. Alban Hall in 1825 due to the influence of Edward Copleston, the provost of Oriel, as part of his design to elevate and improve Oxford teaching as well as his hope that Oriel might acquire the hall. Whately chose Newman to help him in this educational reformation.

Entrusted by Copleston with the task of drawing the timid young graduate out of his shell, Whately took Newman walking and riding and conversed with him at length. As Newman recounts, Whately “was the first person who opened my mind, that is, who gave it ideas and principles to cogitate on”3 and taught him to think for himself. It was from Whately too that Newman imbibed “the idea of the Christian Church as a divine appointment, and as a substantive visible body, independent of the State, and endowed with rights, prerogatives, and powers of its own.”4

Whately was a dedicated if unconventional tutor, often teaching as he lay on a sofa. Known for his challenge to students, “Shall I form your mind, or cram you for a First?,”5 he delighted in nurturing men of talent. He was known in Oxford as the “white bear” as he would scramble around the ditches in Christ Church Meadows wearing a white hat and white coat accompanied by a white dog.

There were several reasons why Whately chose Newman to assist him at St. Alban Hall. Over the previous three years he came to know Newman well and learned to appreciate his many qualities, not least his industry. Moreover, Newman had been a private tutor for a dozen undergraduates,6 some of whom “read” with him during vacations, and had acquired a fine reputation. For his part, Newman accepted the invitation to be Whately’s vice-principal, since he had begun to think his calling might be for college rather than parish—or even missionary—work.

St. Alban Hall

St. Alban Hall, also known as Stubbins, was named after an Oxford citizen, Robert of St. Alban, and established on property he conveyed to a priory of nuns in Littlemore around 1230. When the priory was dissolved in 1525 the Hall was acquired by Cardinal Wolsey, then by the Crown, and finally as an independent academic hall by Merton College. The hall’s buildings were adjacent to Merton, 100 yards away from Oriel, and included a main quadrangle and a smaller court. Rebuilt in 1600 (pictured below) and unaltered until the 1860s, these were the buildings that would have been familiar to Newman.

During its long history, St. Alban Hall had had its fair share of notable principals and students, including the Catholic martyr Cuthbert Mayne (1543–1577), but by the early nineteenth century it was in a parlous state. Its members had often been unable to gain admission to the colleges or else had been expelled from them for disciplinary reasons, and this contributed to its lax regime. In fact, the hall was regarded as the “Botany Bay” of the university, in reference to the penal colony established in Australia.

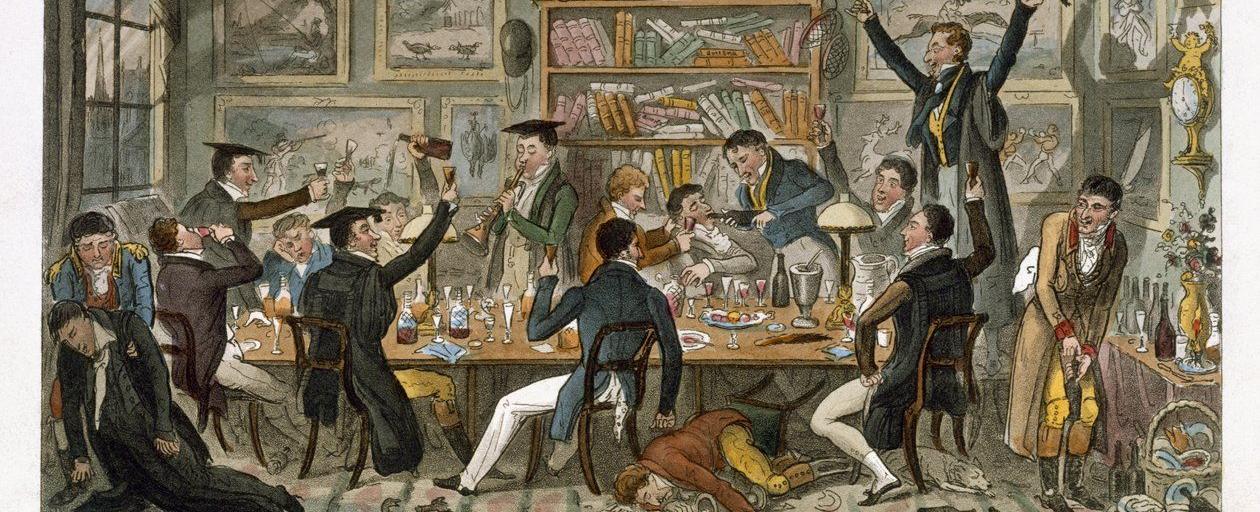

The hall’s notoriety as a haven for idle and bibulous young men was captured by an engraving published in 1824, whose title references the transportations to Australia. Charles Molloy, author of the English Spy, an Original Work, Characteristic, Satirical, and Humorous, Comprising Scenes and Sketches in every Rank of Society (1825), claimed that the scene was “faithfully delineated” from his recollection of a rowdy wine party at St. Alban’s that he and the engraver, Robert Cruikshank, had attended in the early 1820s, shortly before Whatley arrived.7

Trinity revisited

Newman was no stranger to scenes like this, having been an undergraduate at Trinity College, where there was little incentive for the young men to work and where the ruling atmosphere was set by its well-heeled students. Outside the three or four hours of classes each day, there was a great deal of socializing, outdoor pursuits such as hunting and rowing, and a good deal of drinking and gambling. Like most colleges, Trinity was effectively a finishing school for the wealthier classes.

The young John Henry had taken up residence there in June 1817 at the tail-end of the academic year. Within a week of arriving, his preconceptions of Oxford were shattered when he attended a wine party and found himself in the company of undergraduates who enthusiastically set about getting drunk. He told his father, “I really think, if anyone should ask me what qualifications were necessary for Trinity College, I should say there was only one—Drink, drink, drink.”8

If he put this down to end-of-year antics, he was soon disabused of the notion upon his return to Trinity after the long vacation, when he was invited to attend a party with his violin. Upon entering the room, the host announced, “Mr Newman and his fiddle,” to considerable laughter. Rather than a musical social, it turned out to be another drinking party, and he quickly realized that he was invited to be made a fool of, as playing the violin was not considered an accomplishment suitable for a gentleman. After downing three glasses of wine, Newman abruptly announced that he had to leave, and did so, despite protestations. Ten days later, a dozen college rowdies burst into his room, locked the door behind them, and started to tease Newman about working too hard. The ringleader was a huge man who threatened to knock Newman over, but John Henry held his ground—and his temper—and demanded they leave. They did. The next day, the ringleader came to apologize, and they shook hands. Newman had won their respect.9

Though usually able to choose his company and avoid drinking binges, the college’s patronal feast was an exception. The whole college went to Holy Communion on Trinity Sunday, and the following day there was a “grand drinking bout.” Newman left the party early in his first year to avoid getting drunk and in the future refused to attend. In his second year, he sought to bring his influence to bear on his college friends and to boycott the merry making, but the alliance caved in at the last moment, and he was left alone. He remarked, “O how the Angels must lament over a whole Society throwing off the allegiance and service of their Maker, which they have pledged the day before at His Table, and showing themselves true sons of Belial.”10 Nevertheless, he observed that there were indications that the college authorities were keen to raise academic standards and improve discipline. Undoubtedly, he reflected on these observations when he found himself at St. Alban’s.

Testing His Educational Vocation

Newman joined the ranks of the private tutors in 1821 partly with a view to pursuing his dream of remaining in Oxford, partly to support himself and his five siblings after the collapse of his father’s bank in 1816 and the failure of his work at a brewery, followed by a declaration of bankruptcy in November 1821. After his father’s death in September 1824, John Henry took over as head of the Newman family.

We know little about Newman’s months at St. Alban’s as he made only occasional references to his time there in his diary and journal, but it is clear that his work as bursar took up a good deal of his time. It cannot have been an easy for Newman as he must have felt himself out of place overseeing idle young men from wealthy families. Indeed, Whately seems to have exploited his awkwardness on one occasion when he took mischievous pleasure in asking Newman to join him at a dinner, to which he had invited “the least intellectual men in Oxford … men most fond of port.”11

On the first day of term, Saturday 16 April 1825, Newman read prayers for the students in a room at St. Alban’s, which functioned as chapel, hall, and lecture room, then talked to each of them separately. Those he did not manage to see, he interviewed the following Monday. Newman was on his own for the first fortnight as Whately only arrived on 1 May, when he was introduced to the men. Newman oversaw the termly collections (internal exams) and generally acted as a factotum for the principal.

In January 1826, Newman records that he had chronic indigestion due to overwork, and would comment years later that he never recovered from it.12 By then he had effectively served an apprenticeship for a college tutorship, with five years’ experience of private tutoring under his belt and ten months as vice-principal of a small academic hall. His mind was made up, and when offered a tutorship at Oriel on 26 January he accepted. On 21 February, he informed his bishop that he was resigning from his curacy, and on the same day his successor at St. Alban Hall was named, though he continued his duties there until the end of term (15 March). He justified his decision to resign the curacy on the grounds that the tutorship was a spiritual office and a way of fulfilling his Anglican ordination vows. This decision was the result of several years of discernment, coupled with the conviction that the seventeenth-century idea of the college tutor could be revived.

Two years before, on the day after he was ordained a deacon, he wrote in his journal, “I have the responsibility of souls on me to the day of my death.”13 It is appropriate to ask what this meant for him at St. Alban Hall and later at Oriel. In the absence of other evidence, a window into his mind and heart is the way in which he managed to incorporate his academic duties into his prayer life.

After his diaconal ordination, Newman’s prayer routine took a more serious turn. In his personal notebooks, rather than fully written-out prayers, we find a framework incorporating petitions for individuals or groups of people. Each day had its own focus with themes and intentions itemized under three headings: 1) pray for, 2) pray against, and 3) intercede for. On Mondays, under “Intercede for,” Newman wrote: “Oriel College. Provost and fellows (individually) Trinity College, Oxford.” On Tuesdays, “Flock at St Clements.” On Wednesdays, he named nine school or undergraduate contemporaries, as well as “serious men of Oxford” and his private pupils.

No doubt, Newman enlarged this list to include his new charges at St. Alban’s when he became vice-principal, as he was now in the habit of updating his prayer intentions on an annual basis. In his prayer lists for 1835, 1836, and 1837 we find mention of St. Alban Hall (or Alban Hall), alongside Oriel and Trinity. In 1837 Newman composed twenty-two short prayers in medieval Church Latin, one of which includes St. Alban’s:

Custodi, Domine, in die malâ Universitatem nostrum et scholas et collegia ejus, prasertim Collegia SS Trinitatis et Beatae Mariae Virginis de Oriel, et Aulam S. Albani, ut unusquisque in loco suo vigilet, sobrius sit, in te confidat, te expectet, tibi serviat. Per Dominum.14

[Look after, O Lord, in time of trouble our University and its students and colleges, especially the College of the Most Holy Trinity and the College of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Oriel, and the Hall of St. Alban, that each one might be vigilant in his place, be sober, trust in you, look for you, serve you. Through our Lord.]

Educational Practice and Writings

The reader of Newman’s educational writings does well to remember that he was not merely a philosopher of education but was someone immersed in the practice of education at Oxford, first at St. Alban’s then at Oriel, and that his thinking derives from exposure to learning environments and from reflection on how best to shape education to match man’s deepest needs.

It is not possible to ascertain the effect he had on St. Alban’s, though it is known that during the period from 1823–1827 numbers increased from a dozen to nineteen and that its members began to appear regularly in the honors lists.15 Whately and Newman were restricted in the reforms they could carry out because the hall they inherited was largely stocked with freshmen, whom they had not chosen or nurtured. Within eighteen months of his departure, however, Newman was able to take pleasure in seeing that Alban Hall was “rising like a Phoenix,”16 and “rising from its ruins.”17 On his resignation in 1826, Newman recorded in his private journal, “I trust I have done good at Alban Hall,” if for no other reason than by the divinity lectures he had delivered three times a week. He added, “I am very good friends of the men. They saw, I think, they had hurt me.”18 No doubt some of the men of St. Alban Hall had been a handful, but there is evidence that he won over others; his diary shows that he kept in touch with several of them and even invited them to join him for breakfast at Oriel.

No doubt Newman drew on his year at St. Alban’s when he composed a running commentary on his Rules and Regulations for the Catholic University in Ireland, while acting as its founding rector (1854–1858). In offering guidance for the tutors, Newman stipulated that they needed to anticipate in many of their tutees “little love of study and no habit of application,” and to adjust accordingly.19

There are surely echoes of St. Alban Hall in his guidelines for dealing with students “in that most dangerous and least docile time of life, when they are no longer boys, but not yet men.” It was experience that taught him that “the young for the most part cannot be driven, but, on the other hand, are open to persuasion and to the influence of kindness and personal attachment.” His years at St. Alban’s and Oriel taught him to see university residence as “a period of training” linking boyhood and adulthood, which was designed “to introduce and to launch the young man into the world.” It was therefore both a duty and a privilege for the authorities to lead the young men,

to the arms of a kind mother, an Alma Mater, who inspires affection while she whispers truth; who enlists imagination, taste, and ambition on the side of duty; who seeks to impress hearts with noble and heavenly maxims at the age when they are most susceptible, and to win and subdue them when they are most impetuous and self-willed.

This being the case, Newman thought university discipline should be characterized by “a certain tenderness, or even indulgence on the one hand, and an anxious, vigilant, importunate attention on the other.”20

There is no doubt that Newman was an excellent vice-principal at St. Alban Hall because Whately did all he could to retain him in 1826, offering to increase his salary to match that of the Oriel tutorship. In September 1831, on his appointment as Archbishop of Dublin, Whately again offered Newman the vice-principalship of St. Alban Hall, as he was not only resigning the principalship of St. Alban’s but taking his vice-principal with him to be his domestic chaplain. In other circumstances, this offer would have been out of place, but Whately knew that Newman had been deprived of pupils in a row with the provost of Oriel over tutorial arrangements, and that he was available for tutoring elsewhere after the summer of 1831. Newman declined the offer, saying he only wanted “to live and die a Fellow of Oriel.”21

1 Newman followed the simple ritual in the Book of Common Prayer for “The Thanksgiving of Women after Child-Birth, commonly called, The Churching of Women.” As most families in the parish were large, churchings were regular events.

2 Whately acknowledged Newman’s contribution in fulsome fashion in the preface, naming him as one “who actually composed a considerable portion of the work as it now stands, from manuscripts not designed for publication, and who is the original author of several.” Elements of Logic: Comprising the Substance of the Article in the Encyclopaedia Metropolitana with Additions (1827), vi–vii.

3 Newman to Monsell (10 October 1852), LD 15:176.

4 Newman, AW, 69.

5 A. Dwight Culler, Imperial Intellect: A Study of Newman’s Educational Ideal (Yale University Press, 1955), 39.

6 The names are given in LD 1:136.

7 Commentary on Plate 54, History of the University of Oxford: Volume VI: Nineteenth-century Oxford, ed. M. G. Brock and M. C. Curthoys (Oxford University Press, 1997), xxiv.

8 Newman to his father (16 June 1818), LD 1:36.

9 Journal entries (7 and 18 November 1817), AW, 156–57.

10 Newman to W. Mayers (6 June 1819), LD 1:66.

11 Newman, Apo, 73.

12 Diary entry (14 January 1826), LD 1:272. This comment was added at a much later date.

13 Newman, AW, 201.

14 See Vincent Ferrer Blehl, Pilgrim Journey: John Henry Newman, 1801–1845 (Burns and Oates, 2001), 407–31 and Gerard Skinner, Newman the Priest: A Father of Souls (Gracewing, 2010), 295–97.

15 M. C. Curthoys, “The ‘Unreformed’ Colleges,” in History of the University of Oxford: Volume VI: Nineteenth-century Oxford, part 1, eds. M. G. Brock and M. C. Curthoys (Clarendon, 1997), 148.

16 Newman to his sister Harriet (18 October 1827), LD 2:30.

17 Newman to his mother (18 October 1827), LD 2:31.

18 Newman, AW, 208.

19 “Scheme of Rules and Regulations” (April 1856), My Campaign in Ireland, Part 1: Catholic University Reports and Other Papers, ed. Paul Shrimpton (1896; Gracewing, 2021), 117 and 120.

20 Ibid., 114–17.

21 Newman to S. Rickards (30 October 1831), LD 2:371.

Share

Paul Shrimpton

Paul Shrimpton teaches at Magdalen College School, Oxford. Over the last thirty years he has published articles, chapters and books on Newman and education. His Newman and the Laity will appear in 2025.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS