Reflecting on Newman’s Life at the Time of His Death - Part 1. In Memoriam Literature

John Henry Newman died on 11 August 1890, and in October of that year, the Dublin Review published an article celebrating the life and accomplishments of Newman. The article titled, “John Henry Cardinal Newman,” includes four major segments that are now individually republished in the Newman Review for the 135th anniversary of Newman’s death.

The first segment, “In Memoriam Literature,” provides a brief sketch of Newman’s life and an overview of memorial literature dedicated to Newman.

1.—IN MEMORIAM LITERATURE.

JOHN HENRY CARDINAL NEWMAN

On the evening of Monday, August 11, 1890, died, in his own Oratory of St. Philip Neri, Edgbaston, and at the patriarchal age of ninety years, John Henry Newman, Cardinal Deacon of the Holy Roman Church, with the Title of San Georgio in Velabro, for whose loss the deep sorrow not only of the Catholics of these lands, but it may be said of the English people everywhere is yet fresh and vivid,—Requiescat in pace. His end was, perhaps to an ideal extent, such as he himself would have desired. It matters little where one dies or when, as he well knew who had thought so often of death, but even as to this men have their fancies and their prejudices. We believe that the saintly Italian Passionist priest who baptised Newman hoped his end might come at his work; and certainly another saintly priest also a Passionist, Father Ignatius Spencer, the zealous apostle of prayer for England, hoped, as his own choice, that he might die in harness and with swift blow; and, interestingly enough, Father Dominic died on a railway platform, and Father Ignatius fell by the wayside alone. Cardinal Newman’s death, however, was happily otherwise. He fell asleep peacefully in that home he so dearly loved, and of which he spoke so touchingly when last he came back to it after a brief sojourn in Rome; with his brethren—of one of whom it has been said that he was “more to the lonely celibate than a begotten son”—around him to comfort and to pray; at peace with the outside world, having outlived its misunderstandings, its anger and resentment for his acts and words of an earlier time; with many old and long disrupted friendships re-formed in the warmth of a pleasant evening of life, and with the echoes still lingering in the air of those acclamations of love and esteem which, both within and without the Church, rang like music around him as he came back to Protestant England an English Cardinal, universally beloved, respected, honoured—could there have been an ending to life very much more to his heart’s wish? Still more, perhaps, as to its inward and spiritual aspect was it such as he had hoped for. In one of those beautiful sermons in his “Discourses to Mixed Congregations”— “the first work,” he said, “which I publish as a Father of this Oratory of St. Philip Neri” —he wrote, now more than forty years ago:

O my Lord and Saviour, support me in that hour in the strong arms of Thy Sacraments, and by the fresh fragrance of Thy consolation. Let the absolving words be said over me, and the holy oil sign and seal me, and Thy own Body be my food, and Thy Blood my sprinkling; and let sweet Mary breathe on me, and my Angel whisper peace to me, and my glorious Saints, and my own dear Father smile on me; that in them all, and through them all, I may receive the gift of perseverance, and die, as l desire to Iive, in Thy Faith and in Thy Church, in Thy service, and in Thy love. (Discourse vi. "God's Will the End of Life.")

Surely his end was even as he had prayed; and his soul is already, as we trust, within those gates, to reach to which he had asked his friend to pray:

That I may find the grace,

To reach the holy house of toll,

The frontier resting-place.

To reach that golden palace gate,

Where souls elect abide,

Waiting their certain call to heaven

With Angels at their side.

In such direction go our thoughts in the first days of bereavement and mourning. As Catholics we cannot but seek and find consolation in the remembrance of his Catholic life and virtues. With gratification, and with gratitude also to the Father of mercies, do we linger over the story of how, long ago, he departed from friends and associates, from studies and interests, and from that Oxford which had so long been his home, when “the word of the Lord came to him as it did to Abraham of old.” It is a joy, as it is a lesson, to recall how humble he was; how absorbed in the great act when, daily he offered the tremendous Sacrifice at the altar of God; how as the end drew nigh, and he could no longer celebrate daily Mass, he found his consolation in telling his beads, refreshing his soul in the contemplation of the mysteries of Our Lady’s rosary. By such remembrances is he linked to the affections of Catholics who never knew his face or heard his voice, more closely than he could ever have been for merely his intellectual gifts, or his splendid writings, or even for his tender heart, transparent truthfulness, and chivalrous honour.

Forty-five years ago this October, the grace of conversion came to him. The “Kindly Light” showed him the vision of Rome, the Jerusalem of the new covenant exactly at a time midway in the span of his earthly pilgrimage, in the maturity of his powers, in the stability of manhood, with the ties and associations of a lifetime formed and entwined round his heart in an abundance that might well have been itself taken for a divine benediction. Was the light now a “kindly” one? Not apparently perhaps; but with a faith even us that of Abraham Newman followed it. How touching those words which he wrote in 1871 as to the great step of his secession from the Anglican communion, showing as they do his spiritual instincts, and the fidelity of his soul to God’s inspirations.

“As to your question,” he wrote to a lady correspondent, “whether if l had stayed in the Anglican Church till now, I should have joined the Catholic Church at all, at any time now or hereafter, I think that most probably I should not; but observe, for this reason, because God gives grace, and if it is not accepted He withdraws His grace; and since of His free mercy, and from no merits of mine, He then offered me the grace of conversion, if I had not acted upon it, it was to be expected that I should be left, a worthless stump, to cumber the ground, and to remain where I was till I died.”1

Words these which also suggest how strong all those ties and feelings held him, that if not broken while the spirit of the Lord was upon him, would have held him triumphantly when left to himself. But “I have not sinned against the light,” he said in 1833, trying to assure himself, thus, that he should not yet die. Certain do we feel that to the end, he never sinned against the light: Et lux perpetua luceat ei, Domine!

Of the “in memoriam” literature which we have placed at the head of these remarks, we need say very little by way of explanation. The books and articles there named, form but a fraction of the studies of Newman or the tribute to his memory, which since his death, have abounded in book, magazine, and newspapers everywhere. We have taken a few of the more important ones by Catholics, not as disparaging or underesteeming the others, but because these are more likely to be the ones our more distant readers will look to us to mention at the present time.

The Bishop of Clifton’s funeral oration, even deprived of the emotion visible in its delivery, reads admirably. Simple in its language, but full of admiration for the subject of it, and of kindly appreciation, it gives a brief sketch of his career, and a touching reference to some of his good qualities and virtues. The Bishop had long known the late Cardinal, and had, as he mentions, served his first Mass in the chapel of Propaganda, Rome, on Corpus Christi day, 1847; and he was competent to speak of his life as a Catholic. His Lordship made a good point in quoting from the well-known sermon “Christ on the Waters,” the fine description of the Anglo-Saxon character when transformed by Grace, to apply it as the best panegyric of the Cardinal himself.

The Almighty Lover of Souls looked again, and He saw in that poor forlorn and ruined nature .... what would illustrate and preach abroad His grace if He took pity on it. He saw in it a natural nobleness, a simplicity, a frankness of character, a love of truth, a zeal for justice, an indignation at wrong, an admiration of purity, a reverence for law, a keen appreciation of the beautifulness and majesty of order—nay, further a tenderness, and an affectionateness of heart which he knew would become the glorious instrument of His high will, illuminated and vivified by His supernatural gifts.2

A somewhat fuller sketch of the life of the Cardinal is Dr. W. Barry’s “Outline,” which appeared a few days after his death as the Tablet leader, and is now reprinted and published in the C.T.S.’s penny series. Suffice it to say that it is an excellent brief sketch. We shall presently quote a sentence from it which will serve as a specimen of the style in which it is written. Of the magazine articles which we have named on our list, Mr. Meynell’s, as one would anticipate, is full of admiration for his subject, brightly written, and with plenty of illustrative reference. One characteristic paragraph will show its style, and also what it contains deserves to be recorded:

Beautiful were the tributes which Newman’s death elicited from the conspicuous pulpits of Anglicanism, and most affecting to Catholics; but some of the preachers strangely misunderstood their man when they hinted, as Canon Knox-Little did, that Newman would never have left Anglicanism in 1845, had he foreseen how many Roman collars would be worn, how many beards be shaved off, how many “celebrations” be talked about, and confessions heard in the Establishment in 1890. Why, the Arians in their day had Bishops, and Masses, and organisation as perfect as that of the orthodox; but it was with Athanasius, that Newman ranged himself while still an Anglican, and it was precisely the parallel he found between Anglicans and Arians, or Donatists, that brought him at last from Oxford to Birmingham.

It was, in truth, to the Canon Knox-Littles that he addressed himself when he said:

“Look into the matter more steadily; it is very pleasant to decorate your chapels, oratories, and studies now, but you cannot be doing this for ever. It is pleasant to adopt a habit or a vestment; to use your office-book or your beads; but it is like feeding on flowers, unless you have that objective vision in your faith, and that satisfaction in your reason, of which devotional exercises and ecclesiastical appointment are the suitable expression. They will not last in the long run, unless commanded and rewarded on Divine authority; they cannot be made to rest on the influence of individuals. It is well to have rich architecture, curious works of art, and splendid vestments, when you have a present God; but, oh! what a mockery if you have not. If your externals surpass what is within, you are so far as hollow as your Evangelical opponents, who baptise, yet expect no grace. Thus your Church becomes not a home, but a sepulchre; like those high cathedrals once Catholic, which you do not know what to do with, which you shut up, and make monuments of, sacred to the memory of what has passed away.”3

Mr. Lilly’s paper in the Fortnightly, has the unique recommendation of containing a number of Cardinal Newman’s letters, all addressed to Mr. Lilly himself. Mr. Kegan Paul’s thoughtful and beautifully written study, in the New Review, seems to be the outpouring of very deep personal feeling, and is tinged with pathetic solemnity. The writer’s own recent reception into the Catholic Church, a result which he apparently attributes to the influence of one whom he addresses as “dear and honoured Master and Father,” may account for this. It is a brief but very suggestive paper, to be especially recommended.

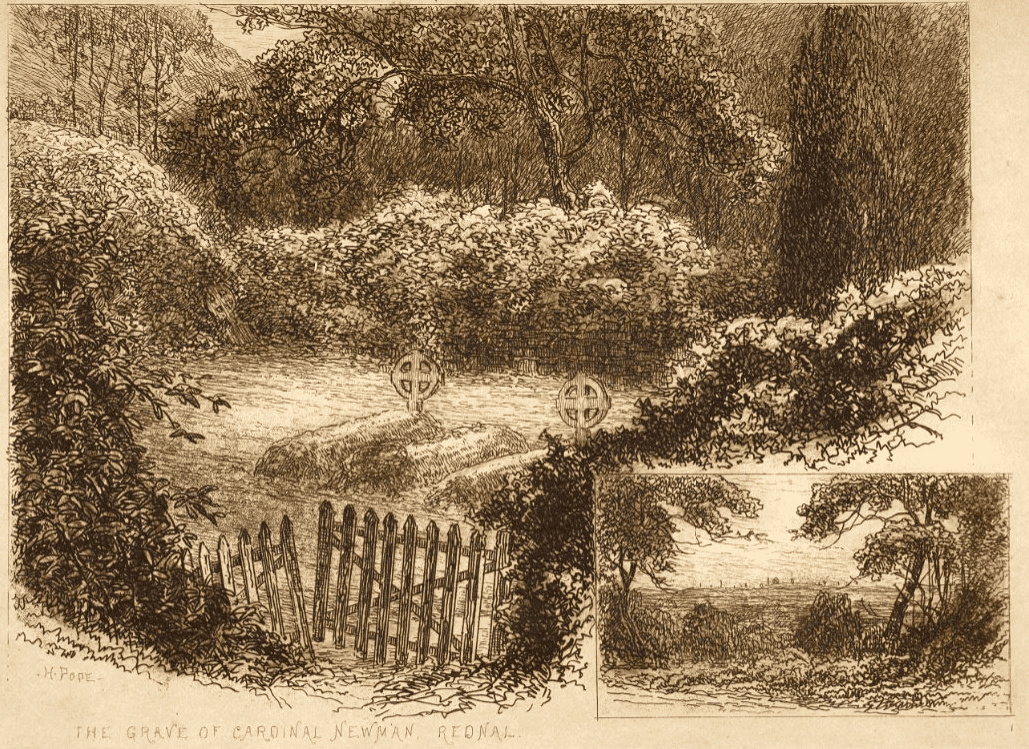

The October number of Merry England is devoted exclusively to the late Cardinal, and is by far the best record of his life which has yet appeared. It forms an excellent memoir pour servir, and there is a wonderful amount of matter in it—anecdotes, letters, reminiscences, &c. —and, as though “John Oldcastle’s” descriptions were not pleasant and graphic enough, there are some admirable photographic illustrations and a facsimile of “Lead Kindly Light.” One of these interesting photographic views is of the last resting-place at Rednal, another is of St. Mary the Virgin, at Oxford, where Newman preached those wonderful sermons, and two other views show us the Birmingham Oratory and the interior of its church. There is still another view worth naming; we have not seen it elsewhere. It is a photograph of the “row of five or six small cottages of one story” which formed the historic “Littlemore,” whither Newman retired after the publication of “Tract 90,” and where, having written the “Essay on Development” to the point where it abruptly breaks off, he was received into the bosom of the Catholic Church. We feel tempted to quote from Mr. Oldcastle one beautiful trait of the last earthly days of the Cardinal, for which we fancy we are exclusively indebted to him:

The end came at last quickly. There had been little illnesses; and the failure of strength was so apparent that it seemed as if a breath or a movement would extinguish the faint spark. On one of these days he asked some of the Fathers to come in and play or sing to him Father Faber’s hymn of “The Eternal Years.” When they had done so once, he made them repeat it, and this several times. “Many people,” he said, “speak well of my ‘Lead, Kindly Light,’ but this is far more beautiful. Mine is of a soul in darkness—this of the eternal light.”4

There remains for us only to call attention to a new and cheap edition of the “Apologia,” which the publishers have opportunely brought out at a moment of special public interest in it. “The boldest and most touching of modern religious biographies,” as Mr. Kegan Paul styles it, is destined to live. It will ever remain, as the Cardinal intended (on his side and from his standpoint) it should—a book of final appeal. It is his own deliberate revelation of his spiritual and mental history, of his herculean efforts to defend the “Via Media,” of the failure, and of its consequences. He had been the Athanasius of the Oxford Movement. But at Littlemore he was called on to act a still more noble rôle: to pay heroic tribute to Truth, by confessing before the world that the principles he had fought to defend were themselves a mistake, and by going over to seek admission into what had hitherto been to him, as it was to them, the camp of the enemy. It was a giant’s effort too; though it may seem to Catholics so very easy a matter. The English Protestant public failed to see the reason of it; later on they even suggested that he, now that he had grown familiar with the Roman camp and had moved behind the scenes, himself regretted it. Repeatedly he protested that he had “never had one doubt” as a Catholic, that he had been “in perfect peace and contentment,” but to little result: it was still supposed that he must regret Anglicanism. Then he wrote what apparently could not be mistaken or misinterpreted:—

I have not had one moment’s wavering of trust in the Catholic Church ever since I was received into her fold. I hold, and ever have held, a supreme satisfaction in her worship, discipline, and teaching; and an eager longing, and a hope against hope, that the many dear friends whom I have left in Protestantism may be partakers in my happiness. And I do hereby profess that Protestantism is the dreariest of possible religions; that the thought of the Anglican service makes me shiver, and the thought of the Thirty-nine Articles makes me shudder. Return to the Church of England! No! “The net is broken, and we are delivered.” I should be a consummate fool (to use a mild term) if, in my old age I left “the land flowing with milk and honey” for the city of confusion and the house of bondage.5

Dr. Barry remarks in his “Outline” that it took ten years to bring Newman into the Church, and that, therefore, “it may well take a century or two to bring the nation.” However, very shortly after the last quoted vehement denial of one species of insincerity, the opportunity of reaching the ear of the British public came to Newman. Kingsley’s charge of untruthfulness was the providential means. Newman, as Dr. Barry puts it, “was allowed to speak, and his countrymen listened.” They listened to the Apologia pro vita sua.

With regard to the three papers which follow in our own pages, we should like to be allowed to thank both Father Stanton, of the Oratory, and Father Lockhart for allowing us to trespass on their busy hours to pen, and that hurriedly, the very interesting reminiscences they have sent us of those early days when they were among Newman’s disciples. Father Lockhart had the glory of “leading the way” and his prior submission to the Church was the immediate reason of Newman’s resigning his pastorate at St. Mary’s. Father Stanton was one of the two, Father F. S. Bowles being the other, who were baptised and received with Newman. We cannot refrain from quoting “John Oldcastle’s” account of the reception; we believe our readers will forgive us the long extract, if only Mr. Oldcastle himself will accept our acknowledgments and do likewise.

These three, “the Vicar” and the two disciples, entered the curious chapel on Thursday afternoon, October 9, 1845, and stood in a line together. Function there was none; and Ritualism hid her face. The bowl of Baptism was of domestic, not of ecclesiastical pattern; and all else was of a tale. Then Father Dominic gave a little address, saying his Nunc Dimittis. Dalgairns and St. John went into Oxford, to the primitive Catholic chapel—St. Clement’s—and borrowed from the old priest, Father Newsham, an altar-stone and vestments, so that Father Dominic might say Mass the next morning—the first and only time at Littlemore. At the Mass the neophytes received their first Communion. The fervour of Father Dominic, when he made his thanksgiving, greatly impressed the converts, who had not been accustomed in Anglicanism to see so much emotion in prayer. One little incident may be recorded as almost comic. On the evening before their reception into the Church, Father Dominic went into the chapel with the catechumens and recited Office with them. But when they came to the record of how St. Denis, after his martyrdom, put his head under his arm and walked about, Father Dominic cried “stop,” and skipped it over. He thought such legends might be a difficulty to beginners, but he did not know his men; for who was more familiar with miracles and the authority assigned to them than the author of those Essays which had made Macaulay exclaim: “The times require a Middleton!” In truth the neophytes were rather scandalized at him, and not at it.6

We do not know what grounds the writer of this passage had for making this last reflection, but it is probably just enough, —if a man of Father Dominic’s, character did cry stop. But the reflection leads us to remark how the legends of the saints had been but a few years before a wonderfully real crux to the writer of Tract 75. That Tract was written by Newman to set before his fellow clergy the general excellence of the Breviary services, and to claim “whatever is good and true in them for the Church Catholic in opposition to the Roman Church, whose only real claim over and above other Churches is that of having adopted certain additions and novelties”— “apocryphal legends of saints” he goes on to call them, which “were used to stimulate and occupy the popular [mediæval] mind.” Even after he had disabused his mind of the idea that Rome exalted our Lady to the disparagement of our Lord (which came about in 1842, as he tells in the “Apologia”), “it was still a long time,” he says, “before I got over my difficulty on the score of the devotion paid to the Saints; perhaps, as I judge from a letter I have turned up, it was some way into 1844 before I could be said fully to have got over it.”7 In the Offices at Littlemore oret had been substituted for ora where invocations of the saints occurred, we believe up to that very day when the Office of St. Denis and his companions was recited with Father Dominic. Let the scandal, however, have been which way it may, it is interesting to note Newman’s affection for the Brievary as early as the year 1836, and whilst he was at the same time denouncing the “Roman corruptions” of it. That Tract 75 is noteworthy as a specimen of his talent as a translator, a subject which, so far as we remember, has not yet engaged the critics. In it he gives an English version of an ordinary Sunday Office, at length; and his verse renderings of the hymns “Nocte surgentes,” “Te lucis ante terminum,” and the others, which have since become so familiar, were, we imagine, written for this occasion. His version of the Confiteor is curious:

“I confess before God Almighty, before the Blessed Mary, Ever-Virgin, the blessed Michael, &c., and you my brethren, that I have sinned too much in thought, word, and deed. It is my fault, my fault; my grievous fault. Therefore I beseech, &c.

He then goes on to translate the lessons, hymns, and special antiphons of the Offices for the Feast of the Transfiguration, and for the Feast of St. Lawrence, deacon and martyr. This part of his task having been faithfully done, even as to the obnoxious antiphons of Our Lady, the writer relieves his Protestant soul by a proceeding at which one cannot help smiling. He adds “a design for a service on March 21, the day on which Bishop Ken was taken from the Church below!” The lessons of the second Nocturn are a life of Ken, and those of the third, on the Gospel (Luke xxii. 25–30), are taken from Jeremy Taylor; and there are hymns, original presumably, but no prayer! The translations given by Newman of these Antiphons of Our Lady, which he says “are quite beyond the power of any defence,” will be found interesting, as indeed is the whole of this singular Tract. Here is the Alma Redemptoris Mater and the Salve Regina, the latter of which the curious may like to compare with the recently authorised version of the Manual of Prayers:

ALMA REDEMPTORIS MATER.

Kindly Mother of the Redeemer, who art ever of heaven

The open gate, and the star of the sea, aid a falling people,

Which is trying to rise again; thou who did’st give birth,

While Nature marvelled how, to thy Holy Creator,

Virgin both before and after, from Gabriel’s mouth,

Accepting All hail, be merciful towards sinners.SALVE REGINA.

Hail O Queen, the mother of mercy, our life, sweetness, and hope, hail. To thee we exiles cry out; the sons of Eve. To thee we sigh, groaning and weeping in this valley of tears. Come then, O our patroness, turn thou on us those merciful eyes of thine, and show to us, after this exile, Jesus the blessed fruit of thy womb. O gracious, O pitiful, O sweet Virgin Mary.

To return, however, from this digression, and to bring these hasty lines to a conclusion, it will be observed that Father Lockhart’s paper is followed by one from the pen of a non-Catholic writer. We willingly give space to Dr. Hayman’s eloquent tribute to the memory of the illustrious dead. He was never, we believe, a disciple of the Cardinal, but had listened to him in the pulpit of St. Mary’s, and knew and revered him. We do not suppose that it will surprise any one to find that to some excellent Anglicans Cardinal Newman’s career as a Catholic was one of perplexing obscurity; but they may be led by the metaphor of the “noble swan frozen in” to conclude that Dr. Hayman is one of those, and there have been not a few at any time in England, who, in Exeter Hall language, would accuse “Romanism” of being intellectual suicide as well as spiritual doom. We, on our part, do not believe Dr. Hayman means anything of this latter kind, but refers, even when he says “frozen in,” to the fact that Newman, as a Catholic, led a life of retirement and inactivity, which, in contrast with his Anglican work, seems obscurity. Perhaps it is perplexing to many that Newman was never sent to Oxford, or, for example, never made a bishop. But apart from these unrealised possibilities, which cannot and need not here be discussed; we may refer to a widespread sentiment which has fastened on the popular mind, to the effect that some sort of numbness weakened his intellectual activity, and arrested his spiritual growth and usefulness. Now, as to the first, we should say that the answer is sufficiently suggested in Newman’s own metaphor of his case— “it was like coming into port after a storm.” Distinctly has he since explained of himself that he could write only under the stimulus of outward emergency. There was plenty of that and to spare in his Anglican days; and tracts and pamphlets, sermons and volumes flowed from his pen. There has been less of it in his Catholic days and from within; but, thanks to Protestants, there has been some. And one such instance we think rather negatives the notion of obscurity. Had Newman not a far larger audience when he wrote his “Apologia” than when he wrote Tract 90?

But we Catholics think he has accomplished one arduous work: and it has a practical and a dogmatic side. On the latter, he never lost his influence on the English public—on the contrary, it has grown with the years since his conversion—and that influence he has uniformly used to bring home to the minds of his countrymen that the claim of the Catholic Church to their obedience is consonant with the Christian dispensation, as it is both legitimate and urgent. Dr. Barry, in his “Outline” has put this forcibly:

One thing he did, with such triumphant success that it need not be done again. He showed that the question of Rome is the question of Christianity. Taking Bishop Butler’s great work for his foundation, he applied to the Catholic Church that “Analogy” which had proved in the Bishop’s hands an irrefragable argument. As, if we hold the course of Nature to be in accordance with reason, we cannot but allow that natural and revealed religion, proceeding as they do on similar laws and by like methods, are founded on reasons too—so, if once we admit that in the Bible there is a revelation from on high, we must come down by sure steps to Rome and the Papacy as inheriting what the Bible contains. To demonstrate this was to make an end to the Reformation, so far as it claimed authority from Scripture or kindred with Christ and His Apostles. When John Henry Newman arrived at that conclusion and followed it up by submitting to Rome, he undid, intellectually speaking, the mischief of the last three centuries. And he planted in the mind of his countrymen a suspicion which every day seems ripening towards certitude, that if they wish to remain, Christians, they must go back to the rock from which they were hewn and become once again the sheep of the Apostolic Shepherd. Cardinal Newman has done this great thing; and its achievement will be his lasting memorial (p. 31).8

But not only has he watered, as it were, with his eloquence, what others might have planted in vain; but in what large measure has not God given the increase, in these our days already, through the influence of his word, of his prayers, of his example. And to have been himself, as it were, the morning-star of the “Second Spring” to his own England—would he deem twenty-five, or even forty-five years, of retirement (not of obscurity) ill spent for such a privilege? We feel reluctant to quote further, but Mr. Kegan Paul’s pathetic words must speak for us, better than we can for ourselves:

Because his works have always been before the public, and because his saintly life has been known, he has continued, even in retirement, to exercise an extraordinary influence on men. “He really died long since; his work has long been over,” writes one. How little they know who thus speak! No intellectual conversion in England or America has taken place in the twenty years of his retirement wherein he has not borne a part, and when converts flew as doves to the windows, his has been the hand which drew them in. There are same who have made their submission to the Church since his death, and the amari aliquid in their joy and thankfulness has been that they could not, in his life, tell him that he was the agent of their conversion, and ask his blessing. . .

Ah! dear and honoured Master and Father, it may be that thou knowest now how largely has that thy prayer been fulfilled, written “on the Feast of Corpus Christi,” twenty-six years ago.

“And I earnestly pray for this whole company with a hope against hope, that all of us who were once so united, and happy in our union, may even now be brought at length by the power of the Divine Will into One Fold, and under One Shepherd.”9

1. Sermon Preached at the Funeral of Cardinal Newman. By WILLIAM CLIFFORD, Bishop of Clifton. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. 1890.

2. Sayings of Cardinal Newman. London: Burns & Oates.

3. Cardinal Newman; a Monograph. By JOHN OLDCASTLE. Being the October, 1890, number of Merry England. London: John Simpkins, Essex Street, Strand.

4. An Outline of the Life of Cardinal Newman. By WILLIAM BARRY, D.D. London: Catholic Truth Society.

5. Apologia pro Vita Sua: being a History of his Religious Opinions. By JOHN HENRY CARDINAL NEWMAN. [New and Cheaper Edition.] London and New York: Longmans, Green & Co. 1890.

6. Magazine Articles:— “Cardinal Newman and his Contemporaries” (the Contemporary Review), by Mr. Wilfrid Meynell; “Cardinal Newman” (the New Review). by Mr. C. Kegan Paul; “John Henry Newman” (the Fortnightly), by Mr. W. S. Lilly, &c.

1 John Henry Newman to Mrs. Houldsworth (3 July 1871), LD xxv, 353.

2 Newman, “Christ Upon the Waters.” (Birmingham: M. Maher, Catholic Bookseller, 27 October 1850), 7.

3 Wilfrid Meynell, “Cardinal Newman and His Contemporaries,” The Contemporary Review 58, (September, 1890): 322–23.

4 John Oldcastle, “Cardinal Newman: A Monograph,” Merry England 15, (October, 1890): 56.

5 John Henry Newman to the editor of the Globe (28 June 1862), LD xx, 216.

6 Oldcastle, “Cardinal Newman,” 28–29.

7 Newman, Apologia Pro Vita Sua: Being a History of his Religious Opinions (Longmans, Green, & Co., 1890), 196.

8 William Barry, An Outline of the Life of Cardinal Newman (Catholic Truth Society), 31–32.

9 C. Kegan Paul, “Cardinal Newman,” The New Review 3, no. 16 (September, 1890): 215.

Share

Angela Baker

Angela Baker was an intern at the National Institute for Newman Studies (NINS) during the summer of 2024, and now serves as the Digital Humanities and Editorial Specialist at NINS.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS