Blessed Jacques-Désiré Laval and the Island of Mauritius

This letter dated 24 May 1848, the original from Rev. Libermann (1802–1852) to Cardinal Wiseman (1802–1865), is famous in the Congregation of the Holy Spirit for the copy made by the Society of the Holy Heart of Mary’s1 (1841) founder, who three months later brought about the merger of this society of priests with the Congregation of the Holy Spirit,2 which was founded by Claude Poullart des Places on Pentecost in 1703.

Libermann reveals the financial situation of the first missionaries to serve the enslaved people freed thirteen years earlier in 1835,3 who were often rejected in favor of the mainly Indian recruits. He indirectly evokes the climate in which his missionaries, Frenchmen in the service of a Catholic community, had to work. Given the constant threat of war between England and France and the Francophobia of the administration, relations were extremely tense. In 1810, the British put an end to the persistent attacks by French privateers from the prosperous Isle of France4 against their merchant ships bound for Asia. They secured victory over Napoleon, who had to cede Mauritius, among other territories. This marked the end of French hegemony in the region. On the French and Mauritian side, the situation is still summed up today by a laconic phrase: “The English stole Mauritius.” On paper, however, the British undertook to maintain the language, customs, laws, and religion of the French colonists.5 By favoring Anglicization, the English were far from winning the hearts of the Mauritians. This Anglicization promoted English as the administrative language for both government and schools, Protestantism in their efforts to keep unworthy Catholic priests as a wat to discredit the Catholic Church in the eyes of the population, and by doing everything to prevent the arrival of French priests.6

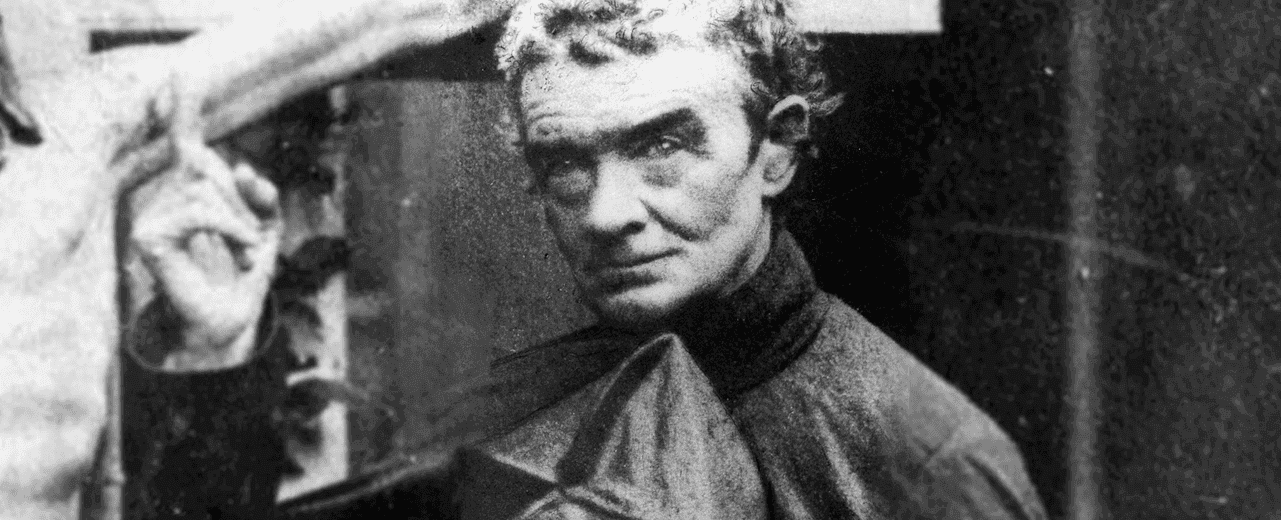

In a situation that Libermann knew well, he asked the English Cardinal Wiseman for help in getting the British authorities to let in additional missionaries and to give his two newcomers (1846 and 1847 respectively) a status like that of Mr. Laval, who first arrived in 1841. Mr. Laval, known by his Anglicized name, Laveil, was a paid prison chaplain, since no one else would volunteer, and was also the only one who initially agreed to look after the lower class.7 After five years of solitary life—although his society demanded community living—the government in England changed, and Laval was finally able to be joined by two other missionaries of the Heart of Mary, and a third arrived at the end of 1848.8

By the time Libermann wrote to Wiseman, all three of them (later to become five with Laval) were living on Laval’s salary alone,9 which was the case until 1856!10 This financial hardship did not prevent Laval from achieving the resounding results that would lead his companions, and subsequently the rest of the Congregation of the Holy Spirit, to imitate his method for work. Laval was eventually beatified on 27 April 1979.11 The letter mentions that “around twenty blacks living as Christians” were present when Laval arrived on the island of Mauritius in 1841, amid the general depravity described by many historians.12 Libermann praises the work carried out on the island, although Laval had to remain alone. Libermann also mentions an “enclosed document,” which would clarify that “[Laval] managed to form a beautiful and fervent Christianity.” The document is missing, but in a letter dated at the end of 1847, Thévaux mentions no less than 7,000 converts! 13 Enthusiastic about the task accomplished, the newly arrived missionaries noted that “he was the one who did it all.”14

Laval’s originality lies in his reliance upon the catechists and treasurers he trained, which was the original reason for the pastoral success on Mauritius. Laval’s influence is evidenced by the 40,000 people who were drawn to his funeral in 1864.15 Through him and those who came to help him, the emancipated enslaved people discovered how much they were loved, and they responded to that love beyond all hope. Chapels, small communities, and then permanent churches flourished over the years. Laval’s companions imitated him and to this day continue to be admired by both the people of the island and by the rest of the Church, which is exemplified by John Paul II, who “placed his pontificate under the protection of this humble missionary.”16

1 The society that Libermann founded was dedicated to “l’Œuvre des Noirs (the Works for the Blacks),” the salvation of the souls of Africans, particularly emancipated enslaved people.

2 After the merger in 1848, the full name became: “Congregation of the Holy Spirit under the protection of the Immaculate Heart of Mary.” Father Libermann then became its 11th Superior General.

3 In 1833, the British government finally adopted the Slavery Abolition Act, which declared the abolition of slavery in all British colonies. It would be several months before Mauritius followed on 1 February 1835, becoming the last of the British colonies to abolish slavery.

4 “Isle de France” was the name given by the French in 1715 to Mauritius, the name originally given to the island by the Dutch in 1598 and restored by Great Britain in 1814.

5 Article 8 of the Capitulation Act of 1810 specified that the colonists could retain “their religion, laws and customs.” Although this was not formulated in the 1814 Treaty of Paris, the new British administration, led by the Governor, Sir Robert Farquhar, agreed that the use of the French language was one of the “customs” and that the inhabitants could continue to use their language, religion, laws, and traditions.” https://histoiresmauriciennes.com/bicentenaire-traite-paris/

6 Historians interested in Laval report difficulties Libermann had in sending missionaries to Mauritius, especially the French missionaries, who had a particularly difficult time due to the anti-Catholicism of Governor Gomm, who wished to Anglicize the freedmen by supporting Methodist schools. See, Joseph Michel CSSp, Le Père Jacques Laval (Beauchêne, 1988), 192. The situation improved after the resolution of the “Éggermont affair,” which revealed the bad faith of the governor and finally made it possible to send two companions to Laval to support him in his task and allow him to live in community in accordance with the rule of his religious society.

7 The British accepted him because they wanted this class of formerly enslaved people to be “moralized.” Laval, as a disciple of Libermann, came to look after the poorest and most neglected, which was characteristic of the congregation. He therefore learned Kreol, their language, a creole of French. It was the class of emancipated enslaved people who were particularly neglected. To give an idea of the condition of freed enslaved people: “The end of slavery was greeted with little joy by the slaves, especially as they were obliged to continue working without pay throughout the so-called apprenticeship period, which lasted until 1839. [...] The most to be pitied were the emancipated slaves. They found it difficult to adapt to their new way of life and virtually nothing was done, either materially or morally, to facilitate their integration.” Fr. Joseph Michel, C.S.Sp., Le Père Jacques Laval, Le Saint de l’Île Maurice, 1803–1864 (Éditions Beauschene, 1976). On the status of Joseph Michel, see Amédée Nagapen, “Joseph Michel, Le P. Laval et l'île Maurice,” Mémoire Spiritaine Journal n° 4, 2e (semestre 1996): 117 à 129. This article remains the most serious and comprehensive study of the apostle of Mauritius to date. Since its publication in 1976, it has become the standard reference work for anyone wishing to work on Laval. See also, Hym Bernard and Lindsay Édouard, À la découverte du Père Laval : ses écrits et récits des témoins (diocèse de Port-Louis, 2023), 72–73; See also, https://histoiresmauriciennes.com/abolition-de-lesclavage-le-gout-amer-de-la-liberte/

8 Lambert (December 1846) and Thévaux (October 1847) are those mentioned in the letter. Thiersé (September 1848), then Bourget and Baud came later. In this letter to Wiseman, Libermann mentions some of the administrative hassles, including permission to stay on the island that had to be renewed every three months, etc., to which his French missionaries were subjected. Also mentioned is the difficulty of finding non-French missionaries.

9 Michael O’Carroll, C.S.Sp., Blessed Jacques Désiré Laval: Apostle of Mauritius (1978): “Nothing came either of

Libermann’s approach to Wiseman, archbishop of Westminster, with a view to overcoming the obstacle of French nationality. The suggestion this time was that Wiseman should try to use his good offices with the government to obtain British nationalisation of French missionaries working in Mauritius: they would become British citizens by deed poll. The government rejected Wiseman’s request.”

10 A Collective, Jacques-Désiré Laval, Apôtre des Noirs à l’Île Maurice (J. Mersch, 1912), 31. Since independence (1968), the Mauritian government has adopted the British practice of paying ministers of any religion in proportion to the number of worshippers.

11 Father Jacques-Désiré Laval was beatified by Pope John Paul II on 29 April 1979 in St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. See the homily for the beatification.

12 Delaplace F. Pivault JM, “A Letter from F. Laval written in Port-Louis on 22 Feb. 1842 to his former Director and to the zealots of the Congregation of the Holy Heart of Mary,” in Le P. Jacques-Désiré Laval, apôtre de l’Île Maurice (1803–1864) (Beauchesne, 1930), 132. A Letter from F. Laval written in Port-Louis on 22 Feb. 1842 to his former Director and to the zealots of the Congregation of the Holy Heart of Mary. Laval writes: “J’ai à vous parler de nos pauvres Noirs […] Il y en a environ quatre-vingt mille dans l’île ; peut-être plus de la moitié ne sont pas baptisés, et ceux qui le sont ne se conduisent pas mieux que les idolâtres de toutes nations. Il n’y en a presque pas de mariés à l’église. Ils se quittent et se prennent plusieurs fois. Ils sont adonnés beaucoup à l’impureté et à l’ivrognerie, et à tous les plaisirs de la chair ; il y a un luxe et une vanité qui dépasse l’imagination.” EN: "I have to tell you about our poor Blacks [...] There are about eighty thousand of them in the island; perhaps more than half are not baptized, and those who are behave no better than the idolaters of all nations. Hardly any of them are married in church. They leave and take each other many times. They are much given to impurity and drunkenness, and to all the pleasures of the flesh; there is a luxury and vanity beyond imagination."

13 Joseph Michel C.S.Sp., Le Père Jacques Laval (Beauchêne, 1988), 216.

14 Michel, Le Père Jacques Laval, 216n1. Michel quotes the letter of 6 December 1847 from Thévaux to Libermann.

15 A Collective, Jacques-Désiré Laval, Apôtre des Noirs à l’Île Maurice, 40.

16 “The parish priests […] even admitted that the main source of their own zeal was none other than the example set by Laval and his confreres.” Michel, Le Père Jacques Laval, 262–63.

Share

Jean-Michel Gelmetti

Jean-Michel Gelmetti, C.S.Sp., holds an MA in Multimedia Studies from Duquesne University (2005–2008). Before that, he completed a License Ès Lettres, Littérature & Sciences Humaines (1973) at Metz before joining the Spiritans in 1980. After a Licensia Docendi in philosophical and theological studies at Sêvres (Facultés Loyola Paris), he was ordained a priest on 28 August 1988. From 1988–1996 he was a missionary in Angola, from 1996–2005 he was editor of Pentecôte sur le Monde magazine, from 2008–2011 he was pastor in Lorraine France in the diocese of Metz. In 2011 and 2012, Gelmetti was part of the formation team in Tanzania. From 2013–2019 he worked at Duquesne University on the production of videos for the US Spiritan Province and later worked at the Duquesne Center of Spiritan Studies for Spiritan Horizons journal until 2024. He is now appointed to the Spiritan Community in Lille (France) where the Spiritans run a parish and a Formation House.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS