Guardians of the Faith: Merry del Val, Vaughan, and the Battle Over Catholic Education in the 1890s

Before a person reaches this last step [becoming a Catholic], he has spent perhaps a lifetime, sensibly or insensibly, alternatively advancing and standing still, balancing, doubting, inquiring.

– Cardinal Herbert Vaughan, 19011

The intersection of Catholicism and education raised important, yet controversial, questions and prompted many discussions in the nineteenth century. Increased freedoms for Catholics in England opened many educational, financial, and societal opportunities. They could attend prestigious universities and finish degrees without professing Protestant oaths or having religious examinations.2 However, these freedoms led to intense debate between Church leaders about 1) how to protect the faith of young Catholics, 2) ensure they received instruction approved by the Church, and, most importantly, 3) how to mitigate the spread and effects of modernist thinking. Such conflict came to a head in the 1890s during discussions of the Commission examining the validity of Anglican Orders. Cardinal Raphael Merry del Val and Cardinal Herbert Vaughan played a significant role in the commission's exploration of this question. A close examination of their correspondence in the 1890s reveals their protectionist views of Catholicism, especially concerning education.

Argued here is that Merry del Val’s letters, while primarily situated around the Commission on Anglican Orders, reveal prominent issues and anxieties about Catholic education. These concerns effectively fit into the larger context of the modernist crisis, such as what the Catholic Church’s identity should be at the turn of the nineteenth century. Should it shift toward modernist thinking and open up to new ideas, or should it maintain its traditional position and evade these new thoughts at all costs? Merry del Val referred to his conflicting views with liberal thinkers, initiatives to establish Catholic affiliations with prestigious universities, and consistent disdain for modernist ideas spreading throughout England and the United States.

Cardinal Raphael Merry del Val

Raphael Merry del Val was born 10 October 1865, at the Spanish Embassy in London to Rafael Carlos Merry del Val, secretary at the embassy, and Sofia Josefa de Zulueta. As a child, Merry del Val traveled across Europe, where he accompanied his father on his diplomatic duties. He returned to the United Kingdom in 1883 to attend Ushaw College in Durham. On the completion of his formal education, Merry del Val’s father presented him to Pope Leo XIII, and the pope insisted he be sent to Academia dei Nobili Ecclesiastici for his religious training.3

Merry del Val is notable for his quick ascension within the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. In 1891, less than three years after his ordination, Leo XIII appointed him as a papal chamberlain, with the title of Monsignor for his excellence within the Catholic bureaucracy.4 Additionally, Merry del Val represented the Holy See at major international events, including serving as a delegate at Queen Victoria’s Jubilee and as secretary to the papal nuncio at the funeral of the German Emperor William I.5 In 1892, he received an appointment to reside in the Vatican.6 Such experiences early in his career likely exacerbated his opinions about Catholic education, as more experience and his growing authority gave him additional avenues for influencing fellow Catholic leaders.

Commission on Anglican Orders

Other positions throughout his career set the stage for Merry del Val to influence major discussions within the Catholic Church. Soon after assuming residence at the Vatican, Merry del Val received another appointment to serve as secretary of the commission investigating the validity of Anglican Orders.7 His work on this committee is the main concern of his correspondence with Vaughan, who seemed to have a mentorship relationship with Merry del Val.8 The pair’s close relationship likely contributed to and exacerbated their strict views on the question of education, as is evident in their correspondence.

It is also important to note that Merry del Val is a polarizing figure within Catholic historiography. Despite many scholars acknowledging his administrative ability and a strong commitment to the Church, other modernist thinkers during the 1890s regarded him less favorably, and he has even been described as an “evil genius.”9 Merry del Val maintained an openly hostile attitude toward Anglicans during his tenure on the commission and attacked anyone who held differing beliefs from him.10 His correspondence with Cardinal Vaughan displayed this hostility, as he frequently critiqued Abbe Fernand Portal and other individuals for their attempts to sway the pope’s decision on the question of Anglican Orders.

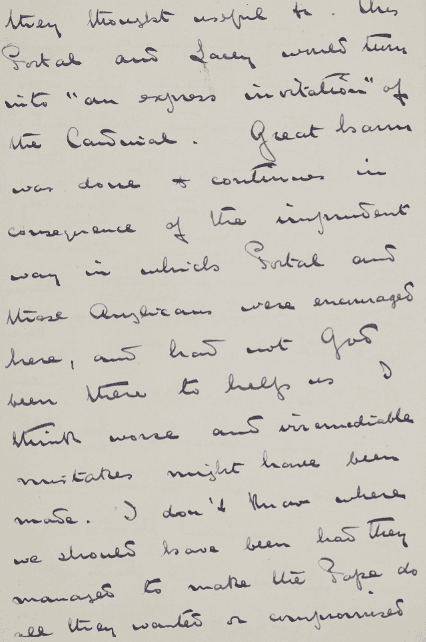

[ . . . ] Portal and Lacey would turn into “an express invitation” of the Cardinal. Great harm was done to continue in consequence of the imprudent way in which Portal and those Anglicans were encouraged here, and had not God been there to help us I think worse and immediable mistakes might have been made. I don’t know where we should have been had they managed to make the Pope do all they wanted

Cardinal Herbert Vaughan

Herbert Vaughan was born on 15 April 1832, in Gloucester to Colonel John Francis Vaughan and Louisa Eliza Vaughan (Rolls).11 Vaughan began his theological studies in 1851 at the Collegio Romano in Rome. He was ordained as a priest in October of 1854. Following his ordination, Vaughan received an appointment as Vice President of St. Edmund’s College in Ware.12 However, a ruling from Rome soon removed him from this position.13 After his dismissal, he formed the Missionary Society of Mill Hill in the 1860s to train and send missionary priests worldwide as a way to introduce Catholicism to less developed countries.14 During his endeavors with the missionary society, Vaughan purchased the Catholic newspaper The Tablet in 1868. Before his purchase, The Tablet faced significant financial constraints and political debate between Catholic liberal and conservative viewpoints. Vaughan would use the publication as a way to limit the spread of liberal viewpoints to the general Catholic public.15 In 1872, he was consecrated as Bishop of Salford in northwest England, serving there for twenty years until his appointment as Archbishop of Westminster in 1892, where he served until his death in 1903.16

Throughout his life, Vaughan had both interest and involvement in shaping Catholic education in England. After he traveled across the United States and Europe, he became interested in specialized colleges. For example, in Manchester in 1876, he created St. Bede’s College, a new institution dedicated to teaching young Catholics about business and commercial skills, while not focusing on the Classical subjects.17 That way, Catholic students not interested in pursuing the priesthood could still attain an education rooted in their religion without external intellectual threat. However, the operation quickly fell apart, as Vaughan traveled away for most of its first year, students of all ages attended, and the location was forced to move during the second academic year.18 Eventually after fifteen years the experiment was abandoned and converted into a traditional classical school. Vaughan’s highly regarded career in education displayed a dedication to crafting and promoting the best for the Catholic youth. However, his devotion also manifested in unfavorable ways concerning other prominent figures’ efforts in the latter part of the nineteenth century.

Throughout his career, Vaughan continuously reiterated his belief that Catholic boys interested in the priesthood should remain separate from all other students, whether Catholic or not. For example, Vaughan intervened in an 1894 scheme to establish a summer school for Catholic teachers at Oxford due to the threat of “mixed education and the frequentation of non-Catholic universities by Catholic youth.”19 According to Vaughan, mixed education would open Catholic youth to other ideas of religion, or, worse, that religion would be deemed unnecessary. Vaughan was afraid that if Catholic youth could attend universities with individuals from all beliefs and backgrounds, their faith would indirectly fall under attack from discussions with fellow students. Letters concerning the university question fueled Vaughan’s strong beliefs favoring Catholic isolation:

For a certain amount of irreligion, nay, for a large amount of it, I was prepared … The danger to us does not lie in constantly hearing open declarations of agnosticism … but in the constant and most insidious assumptions made by all around that there is no supernatural … there is no need of religion.20

His concerns for the faith of the youth also manifested in his perspective on the Church’s involvement in education. Vaughan believed priests played an essential role in education to “inspire children with respect and affection for religion,” pushing them to learn more about and continue practicing within the faith.21 Cardinal Vaughan’s strict beliefs and standards for Catholic education throughout his career signal his lasting commitment to separating Catholic students and protecting their spiritual integrity at all costs. His standards also displayed his viewpoint that the Catholic Church must remain involved and provide such educational avenues for youth, as seen in his later involvements with Cardinal Newman.

Religious Education in the Nineteenth Century: The Oxford Movement and Cardinal Newman’s Connections with Vaughan

Vaughan’s role in education reflected his disdain for Anglicanism and intellectualism, which he saw as inextricably linked, with most Anglican priests being graduates of major universities like Oxford and Cambridge. Accordingly, he wished to limit the educational prospects of young Catholics in England.

Before the mid-nineteenth century, penal laws in England prevented Roman Catholics from attending Oxford or Cambridge. One needed to be a conforming Anglican to attend. However, the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 initially opened these institutions to Catholics on the condition that students would take a Protestant oath before graduating. In 1854, Parliament passed the Oxford University Reform Act, opening the university to all students without theological testing or oaths. Later, the University Tests Act of 1871 abolished requirements for all other schools. Despite the removal of these barriers many parties in the Catholic Church remained suspicious of what they still regarded as Protestant institutions and moved to establish separate Catholic houses. This way, if young Catholics chose to attend these establishments, they could stay within a community of fellow Catholics and thus reduce what they considered as dangerous Protestant influences. While British law no longer limited the higher educational prospects of Catholics’ in the country, many Catholic leaders continued to maintain strict beliefs about Catholic and Protestant/Anglican separation, therefore, reinforcing the barriers that Parliament tore down for them. These artificial barriers to education and their discourse continued throughout the nineteenth century, with Vaughan participating in the most prominent affairs.

The Catholic Universities

The first prominent effort toward establishing a Catholic base at a Protestant university was when John Henry Newman proposed the establishment of an Oratory house at Oxford. Before he converted to Roman Catholicism, Newman received his formal education at Oxford. Prior to his conversion in 1845, Newman was a student, Anglican priest, and Fellow at Oriel College. Following his conversion, Newman believed that establishing a Catholic house at the university would allow young Catholics to have a safe center for their religion while being able to benefit from a university education.22 Newman’s campaign failed because many Catholics, including Vaughan, opposed the Oxford Scheme, which led to a rescript from Rome preventing him from continuing (it would be the 1990s before Oratorians would finally return to Oxford, taking over the city mission of St Aloysius following the resignation of the Jesuits). During this incident, Vaughan notably attacked and attempted to sabotage Newman’s reputation and to tarnish his case for the house.23 Newman later became the first rector of the Catholic University in Ireland, (now University College, Dublin). Before University College, the only institutions in the country were the Anglican-affiliated Trinity College, Dublin, and Queen’s College.24 The Oxford matter was an early example of Vaughan’s long-lasting commitment to his views concerning Catholic education. He sought to prevent “mixing” faiths at all costs, which as we will see, presents in the harsh language Merry del Val utilized in his letters during the 1890s.

Vaughan opposed young Catholics attending these traditional Protestant universities, but he understood that they needed some form of formal education, though only with instruction and oversight from the Catholic Church. Amid the Oxford scheme and following Newman’s campaign, Vaughan supported Cardinal Henry Edward Manning’s failed attempt at establishing a Catholic University in Kensington. It is important to note that one of the reasons the operation failed was due to their exclusion of religious orders, such as the Jesuits, Benedictines, and Oratorians.25 The Catholic University in Kensington, also supported by Vaughan’s close friend, William George Ward, aimed to educate young Catholics solely under Catholic influences. This way, if students ever signaled religious skepticism, the responses from professors would be rooted in Catholicism and would guide them back to “conformity,” as Ward’s son, Wilfrid noted in his reflections on the school.26

The Kensington scheme was offered as an alternative to having a Catholic house at Oxford or Cambridge. Vaughan proposed that bishops and religious bodies at various Catholic colleges should come together to form a Catholic university directly under the Holy See. However, neither Vaughan nor other leaders at the time could secure Newman’s support for this new, separate Catholic university.27

Vaughan continued to maintain strict beliefs on Catholic education following Newman’s failed Oxford scheme, his campaign in Ireland and Manning’s failure at Kensington. In a memorandum from 1889, Vaughan called for a restatement from Propaganda concerning Catholic attendance at Cambridge or Oxford, citing that Catholics of England had long suffered worse conditions and that they should be able to endure the “slight privation for the purity of their faith” by receiving a Catholic education.28 Vaughan’s perspective on Catholic education did not resonate with all Catholic youth, as attending Cambridge or Oxford opened more opportunities than attending a smaller, less prestigious Catholic-oriented institution. Particularly, Maisie Ward, daughter of Wilfrid Ward, gave a platform for Wilfrid’s perspective concerning the impact of limited educational opportunities for Catholic youth:

In cutting me and other Catholics off from the Universities – and it was mainly my father’s influence on Manning which led to our exclusion from Oxford and Cambridge – the ecclesiastical authorities cut off in some cases the most natural avenues to healthy ambition … And as I had no practicable programme set before me, my father’s ideals really tended to prevent my doing anything useful at all.29

The failure of Newman’s campaign for an oratory at Oxford, combined with Vaughan’s strong favor toward establishing a separate Catholic university highlights the conflict within Catholicism over rules and general regulations over education for the youth. Debates over whether Catholics should attend institutions such as Oxford or Cambridge led to failed missions on both sides. Even with these failures, the tension within the debate reverberated throughout the rest of the nineteenth century. More specifically, Merry del Val’s 1890s letters to Vaughan from the 1890s revisited the arguments for Catholic education.

Merry del Val’s Letters

In 1895, both Merry del Val and Vaughan were involved in the commission investigating the question on Anglican Orders. The commission consisted of individuals on both sides of the argument, with Abbe Fernand Portal, Louis Duchesne, and Pietro Gasparri leaning in favor of Anglican Orders, and Vaughan, Merry del Val (serving as secretary), and Canon James Moyes against them.30 Vaughan regarded the idea of a reunion between the Anglican and Catholic Churches as a threat to the Catholic Church in England, and he wanted to ensure the movement failed. Merry del Val, on the other hand, believed that Duchesne, Portal, and other pro-Anglican thinkers picked religion apart in order to preach liberalism.31

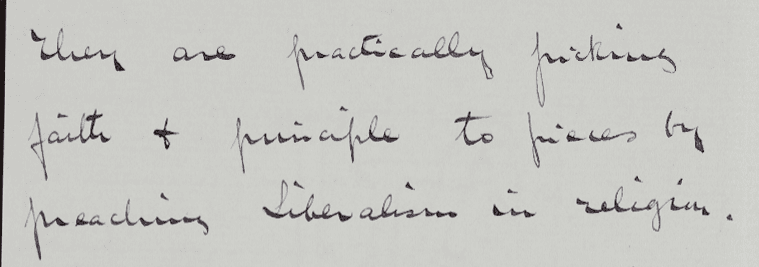

They are practically picking faith + principle to pieces by preaching Liberalism in religion.

If the orders were deemed invalid, leaders like Vaughan and Merry del Val anticipated increased conversions of Anglican clergy to Roman Catholicism.32 Furthermore, they believed that anticipated conversions would push current and future young Catholics away from attending Oxford or Cambridge, potentially propelling an English Catholic university into success. In this case, Catholicism could receive protection from the liberalism that Merry del Val despised so much.

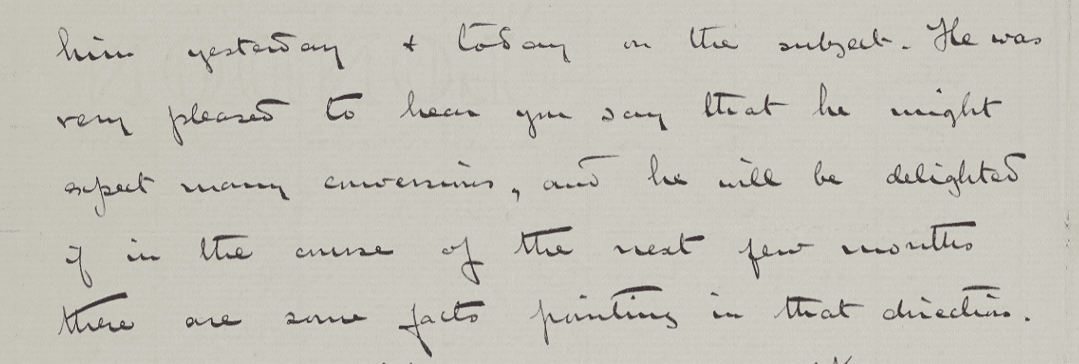

He [the Holy Father] was very pleased to hear you say that he might expect many conversions, and he will be delighted if in the course of the next few months there are some facts pointing in that direction.

Although most of Merry del Val’s correspondence with Vaughan pertained to the mission to deny the validity of Anglican Orders, a few letters reveal further information about issues of Catholic education and fears of modernism during the 1890s. More specifically, Merry del Val alludes to concerns over affiliating Catholic education (in both a secondary school and university setting) with public or non-Catholic institutions. His allusions to St. Edmund’s House at Cambridge and pursuits of Archbishop John Ireland in the United States demonstrates this.

In July of 1899, Merry del Val wrote to Vaughan about a decision made against a “House” and its connections to a “University.” He discussed a campaign to re-examine a question ruled against the house.33 Although not directly mentioned, the “House” is likely a reference to St. Edmund’s House at Cambridge University. The house was formed in 1896 to become a formally recognized Catholic residential hostel affiliated with Cambridge. Furthermore, an 1895 instruction, which reversed the 1867 rescript from Propaganda concerning attendance at these schools, permitted Catholics to reside at the older, prestigious institutions.34 It is important to note that Vaughan had direct involvement in initial discussions about the house. To reiterate earlier points, Vaughan maintained the position that young Catholics were vulnerable when at these institutions and had standards for both St. Edmund’s and any other form of Catholic institute affiliated with a non-Catholic university. Vaughan stated that the houses needed to be led by trustworthy men, have a small number of students, and follow strict guidelines for their studies.35 Despite his reservations, by the mid-1890s Vaughan had started to recognize that young Catholics would continue attending non-affiliated universities even in the face of new restrictions, and he eventually approved the general affiliation between St. Edmund’s and Cambridge.36

In 1898, leaders at St. Edmund’s House sought recognition as a Catholic hostel for Cambridge University, which failed by a vote of 471 to 218.37 Therefore, the house could not establish itself as a formal, external, Catholic body of Cambridge University. However, this did not stop bishops and other institutions from sending students to the house. Furthermore, students who resided at the house organized different club sports and produced a true collegiate environment.38

The house presented Vaughan, Merry del Val, and other figures who were against young Catholics attending non-Catholic institutions with a continuation of the existing issue. Once again, if the operation succeeded and St. Edmund’s did eventually become a formally recognized hostel, they felt it would further encourage young Catholics to attend these institutions. Therefore, the students would be exposed to teachings and life adjacent to Cambridge, potentially “jeopardizing” their faith. It likely reinvigorated concerns from the debate over Anglican Orders. In the eyes of Vaughan and Merry del Val, it remained important to keep as much separation as possible to maintain the authority of the church.39 If the content of Merry del Val’s letter truly is connected to St. Edmund’s, the harsh conclusion encapsulates the general disdain for Catholic and non-Catholic mixing at the collegiate level.40

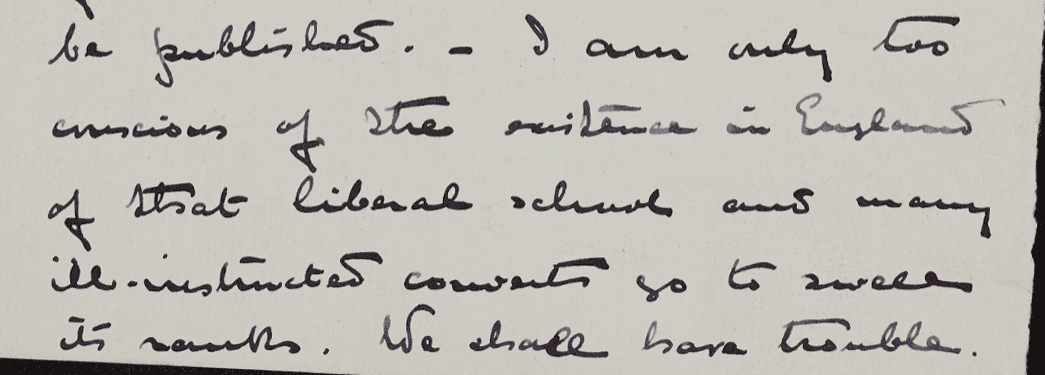

I am only too conscious of the existence in England of that liberal school and many ill-instructed cowards go to swell its ranks. We shall have trouble.

Recent scholarship evaluates the feasibility of Catholic universities in relation to Catholic doctrine and practices. For example, George Dennis O’Brien explores this issue in The Idea of a Catholic University, including quotes from Irish activist George Bernard Shaw concerning Catholicism and education. In Shaw’s view, a Catholic university was contradictory, as Catholicism seems committed to “dogmatic authoritarianism” rather than promoting intellectual freedoms.41 It could be argued that Merry del Val and Vaughan’s policies concerning Catholic education in England support this authoritarian argument.

Concerns Regarding Americanism

Merry del Val also wrote to Cardinal Vaughan about Catholic education in the United States and Canada. In two letters from 1899, Merry del Val referred “Americanism,”42 which Pope Leo XIII addressed in his two encyclicals: Longinqua (1895) and Testem Benevolentiae Nostrae (1899). Longinqua claimed that the United States should be conjoined with the Catholic Church, so that the country could remain moral and seek truth for all its citizens. Testem Benevolentiae argued that the church would not reject everything modern, but it called for Christ and the Catholic Church to act as teacher above all, even the state.

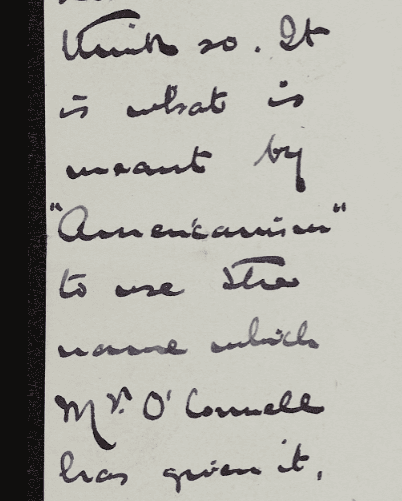

In his letter referring to the house affiliated with a university, Merry del Val questioned whether Leo XIII’s “upcoming release” (i.e., Testem Benevolentiae) should include any information to push Catholics against the school. He argued that the operation is what many would think of as Americanism.43

[ . . . ] It is what is meant by “Americanism” to use the name of which Mr. [Denis] O’Connell has given it.

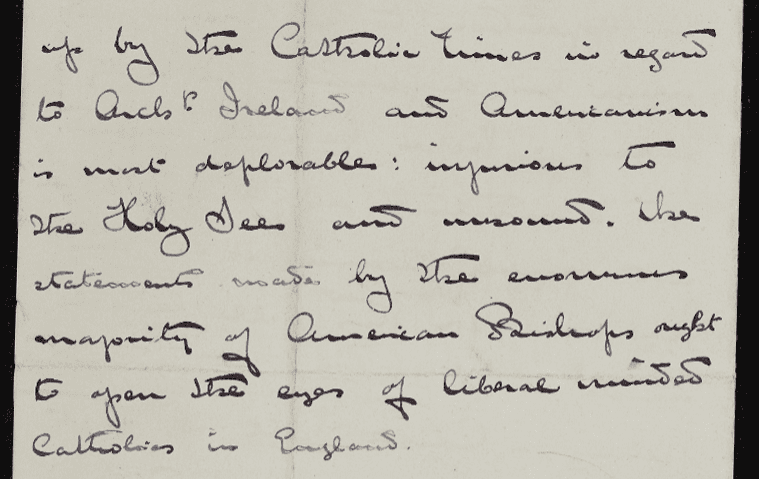

Later that month, Merry del Val wrote another letter in which he discussed an article published in the Catholic Times about Archbishop John Ireland and Americanism. Ireland was the first archbishop of Saint Paul, Minnesota, who was known for his affiliation with Americanism. In the early 1890s, Ireland formulated the Poughkeepsie Plan, to establish Catholic schools in local parishes in Minnesota. These schools received public funding, but religious instruction would only occur after typical school hours.44 Anti-modernist Catholics used Ireland’s policies, along with his support for state schools, to further their campaign against Americanism,45 which provided fuel for those compiling the case for Longinqua and Testem Benevolentiae to address. Another notable Americanist from this era was Monsignor Denis O’Connell, who in 1903 became rector of the Catholic University of America. In 1908, O’Connell was made Bishop of San Francisco. Although Ireland and O’Connell initially worked together, they would later find their views beginning to diverge. According to biographies on Ireland, the growing distance between him and O’Connell marked a differentiation between “old” and “new” Americanism.46

A similar situation also developed in Canada and in 1897 when Leo XIII sent Merry del Val there to assist in bringing about a solution to what was titled the “Manitoba question,” which was a conflict over the separation of Protestant and Catholic schools, independent schools, and their financing.47 Merry del Val drafted a proposed solution that created school districts specifically for Catholic children with specific instruction, an inspector, and ensured that Catholic taxes would be directed to these districts.48

Although we have been unable to obtain a copy of the Catholic Times article, and it is therefore unclear exactly what it stated about Ireland and Americanism, Merry del Val’s conclusion that the statements were “injurious to the Holy See,” and that liberal-minded Catholics should read the article49 indicate a shift in the modernist crisis, one that discredited the thinking of modernists and individuals like John Ireland.

[ . . . ] up by the Catholic Times in regard to Archp. Ireland and Americanism is most deplorable; injurious to the Holy See and around. The statements made by the enormous majority of American Bishops ought to span the eyes of liberal minded Catholics in England.

Merry del Val’s call for liberal Catholics in England to read the Catholic Times article signaled that it contained negative content on the Americanist movement across the pond. That way, the anti-modernist sentiment would win over the public and give him and other high-ranking individuals within the church continued authority over modernist ideals. Any shifts in John Ireland’s thinking and divisions in the “enemy camp” acted as further support for Merry del Val’s campaign against Americanism and modernist thought, and new information concerning Ireland’s changing views allowed Merry del Val to prove the dangers and fragility of modernist thinking within the Catholic Church.

Conclusion

Cardinal Merry del Val’s letters to Cardinal Vaughan embody the complexities of the developing modernist crisis at the end of the nineteenth century. Their involvements and attitudes regarding Catholic education and Anglican relations demonstrate that they maintained their critical stance toward isolating Catholics from other religious groups and even enforcing separation within Catholic schools, between the priestly students from the lay. While their correspondence primarily concerns the commission on the validity of Anglican orders, Merry del Val’s multiple references to Catholic education schemes, such as the operation at St. Edmund’s House at Cambridge and John Ireland’s attempts for public Catholic education in the United States, promotes critical thought and reflection on their careers and beliefs regarding Catholicism and education. Merry del Val’s advocacy for Catholic schools in Canada demonstrates this commitment to ensuring separate education for Catholic students. Furthermore, Vaughan’s involvement in sabotaging Cardinal Newman’s scheme in Oxford and general campaign supporting a separate Catholic university in England display his beliefs against allowing Catholics to attend any institution affiliated with a secular or Protestant environment.

Considering all of these factors, Merry del Val’s letters capture the complex debates over how Catholic education must be handled as well as the tense climate of the modernist crisis. The campaigns of both Vaughan and Merry del Val highlight continued tensions within the Catholic Church concerning tradition or adaptation, both of which remain pertinent to conversations within the Church today. Navigating modernity proves to be difficult in both the turn of the nineteenth century and now, especially in education. Scholars continue to conceptualize the idea of “what a Catholic university is,” with thoughtful research, insight, and critique. Merry del Val and Vaughan’s strict beliefs, actions, and words exchanged within their 1890s correspondence fit well within various perspectives on Catholic universities. Further in-depth research into the pair, Vaughan’s side of the letters alongside Merry del Val’s involvement in the modernist crisis will help to contextualize how the modernist crisis spilled onto English soil. Furthermore, additional inquiry promotes critical thought and conversation concerning the intersection of religion and education throughout modern Catholic history.

1 Herbert Vaughan, “Introduction,” in Roads to Rome: Being Personal Records of Some of the More Recent Converts to the Catholic Faith (Longmans, Green, and Co., 1901), vi.

2 Charles Russell, “Cardinal Raphael Merry del Val: Papal Secretary of State,” The Irish Monthly 32, no. 370 (April 1904): 192-93.

3 Marvin O’Connell, Critics on Trial: An Introduction to the Catholic Modernist Crisis (Catholic University of America Press, 1994), 212-13; Sister Mary Bernetta Quinn, Give Me Souls: A Life of Raphael Cardinal Merry del Val (The Newman Press, 1958), 30.

4 J. Derek Holmes, “Cardinal Raphael Merry del Val: An Uncompromising Ultramontane: Gleanings from His Correspondence with England,” The Catholic Historical Review 60, no. 1 (April 1974): 55.

5 Russell, “Cardinal Raphael Merry del Val,” 193.

6 O’Connell, Critics on Trial, 213.

7 O’Connell, Critics on Trial, 211.

8 Holmes, “Cardinal Raphael Merry del Val,” 57.

9 Arthur McCormack, Cardinal Vaughan: The Life of the Third Archbishop of Westminster, Founder of St. Joseph’s Missionary Society, Mill Hill, (Burns & Oates, 1966), 7, 12.

10 J.G. Snead-Cox, The Life of Cardinal Vaughan (London: Herbert and Daniel, 1910), 2:117-19.

11 O’Neil, Cardinal Herbert Vaughan, 2-3, 173; Snead-Cox, The Life of Cardinal Vaughan 4.

12 Snead-Cox, The Life of Cardinal Vaughan, 1:305-309.

13 Brian W. Taylor, ”John Henry Newman and a Catholic Presence at Oxford,” The Irish Journal of Education 27, nos. 1/2 (Summer/Winter 1993): 41. Furthermore, Taylor notes that Newman initially had an idea to establish a separate Catholic institution from Oxford but moved away from this idea because receiving an Oxford education held more prestige than a brand new institution. Newman’s own words speak to the general difficulty for young Catholics during this time to attend a Catholic-affiliated institution. In An Idea of a University, Newman highlights that “Catholics who aspire to be on a level with Protestants in discipline and refinement of intellect have recourse to Protestant Universities to obtain what they cannot find at home.” For more, see: Newman, “Preface,” in Idea of a University, xv.

14 Snead-Cox, The Life of Cardinal Vaughan, 2:70-72.

15 Snead-Cox, The Life of Cardinal Vaughan, 1:71-72.

16 Snead-Cox, The Life of Cardinal Vaughan,1:74.

17 Snead Cox, The Life of Cardinal Vaughan, 2:194-96.

18 Holmes, “Cardinal Raphael Merry del Val,” 57-58; Cardinal Rafael Carlos Merry del Val to Cardinal Herbert Alfred Henry Vaughan (15 June 1896), NINS Digital Collections.

19 Cardinal Rafael Carlos Merry del Val to Cardinal Herbert Alfred Henry Vaughan (5 July 1896), NINS Digital Collections.

20 Cardinal Rafael Carlos Merry del Val to Cardinal Herbert Alfred Vaughan (5 July 1896), NINS Digital Collections.

21 Garrett Sweeney, St Edmund’s House, Cambridge: The First Eighty Years, A History (Master and Fellows, 1980), 1-3.

22 Sweeney, St Edmund’s House, Cambridge, 9.

23 McCormack, Cardinal Vaughan, 263-65; Sweeney, St Edmund’s House, Cambridge, 7.

24 Sweeney, St Edmund’s House, Cambridge, 25.

25 Sweeney, St Edmund’s House, Cambridge, 28, 30-32.

26 William J. Schoenl does an excellent job describing this fear in the opening pages of his work on the intellectual crisis during the nineteenth century. He states that “one of the functions of the authority in a church is to preserve the fundamental beliefs of that church. This is in itself a conservative function.” For more information on his words and detailed history on the validity of Anglican Orders, see: William J. Schoenl, The Intellectual Crisis in English Catholicism: Liberal Catholics, Modernists, and the Vatican in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (Garland Publishing, 1982).

27 Cardinal Rafael Carlos Merry del Val to Cardinal Herbert Alfred Vaughan (5 July 1899), NINS Digital Collections.

28 Cardinal Rafael Carlos Merry del Val to Cardinal Herbert Alfred Vaughan (5 July 1899), NINS Digital Collections.

29 Cardinal Rafael Carlos Merry del Val to Cardinal Herbert Alfred Vaughan (31 July 1899), NINS Digital Collections.

30 “University Tests Act, 1871,” UK Legislation, The National Archives.

31 Lawrence R. Gregory, A History of St. Bede’s College, Manchester, vols. 1 and 2: 1876-1950 (2024), 1:51-60.

32 Robert O’Neil, Cardinal Herbert Vaughan: Archbishop of Westminster, Bishop of Salford, Founder of the Mill Hill Missionaries (Kent: Burns & Oates, 1995), 95.

33 O’Neil, Cardinal Herbert Vaughan, 407.

34 McCormack, Cardinal Vaughan, 263.

35 McCormack, Cardinal Vaughan, 175.

36 Ward, The Wilfrid Wards, 1:76-77.

37 Paul Shrimpton, A Catholic Eton? Newman’s Oratory School (Gracewing, 2005), 237.

38 Maisie Ward, The Wilfrid Wards and the Transition, vol. 1, The Nineteenth Century (Sheed & Ward Inc., 1934), 46-47.

39 McCormack, Cardinal Vaughan, 23, 30.

40 Snead-Cox, The Life of Cardinal Vaughan, 187-91.

41 Anthony M. Maher, The Forgotten Jesuit of Catholic Modernism: George Tyrell’s Prophetic Theology (Fortress Press, 2018), 54, note 87.

42 George Dennis O’Brien, The Idea of a Catholic University (University of Chicago Press, 2002), 1.

43 Donal McCartney and Thomas O’Loughlin, eds., Cardinal Newman: The Catholic University: A University College Dublin Commemorative Volume (University College Dublin, 1990), 9-10.

44 Marvin O’Connell, Critics on Trial, 292-95.

45 John T. McGreevy, Catholicism and American Freedom: A History (W.W. Norton & Company, 2003), 123-24.

46 Stephen T. Rusak, “The Canadian ‘Concordat’ of 1897,” The Catholic Historical Review 77, no. 2 (April 1991): 229.

47 Rusak, “The Canadian ‘Concordat’ of 1897,” 224.

48 Marvin R. O’Connell, John Ireland and the American Catholic Church (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988), 466-67.

49 Americanism, as Pope Leo XIII describes in Testem Benevolentiae Nostrae, was defined by renewed opinions on both interpreting the faith and drawing others to convert. In that regard, Americanists believed that the Church, particularly in the United States, should relax its strict principles and opinions to follow the “spirit of the age” at that time.

Share

Kaelin Hughes

Kaelin Hughes is a graduate student at Duquesne University, with a focus on American history and a minor in Public History. She served as a Digital Humanities Intern for the National Institute for Newman Studies for the Spring 2025 semester. Outside of her work for the NINS, her personal research focuses on the intersections of disability and labor. She hopes to pursue a career in either academia or an archival setting.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS