Reflecting on Newman’s Life at the Time of His Death - Part 3. 'Tis Fifty Years Since

John Henry Newman died on 11 August 1890, and in October of that year, the Dublin Review published an article celebrating the life and accomplishments of Newman. The article titled, “John Henry Cardinal Newman,” includes four major segments that are now individually republished in the Newman Review for the 135th anniversary of Newman’s death.

The third segment — “Cardinal Newman; Or, ‘’Tis Fifty Years Since” — is an essay by William Lockhart reflecting on Newman’s time in the Catholic Church.

3.—CARDINAL NEWMAN; OR, “‘TIS FIFTY YEARS SINCE.”

Among the many indications marking the different phases of religious thought in England, perhaps none is more noteworthy than the way in which the death of our venerable Cardinal has been received by the English non-Catholic public. The public press, the surest test of public opinion, when all political and religious parties are agreed on any point, has spoken unmistakably its estimate of this great Catholic, and of the work of his lifetime. They have spoken of his death as a public loss, the passing away of one of the grandest intellects of our age, worthy to be ranked with an Origen, an Athanasius, an Augustine—of a soul most lovable and tender, straightforward, honest, and truthful to conscience in all that he has done or written.

But the words of our beloved Cardinal Archbishop, spoken in the London Oratory, at the Solemn Mass of Requiem, say all this better far than words of mine.

If any proof were needed of the immeasurable work that John Henry Newman has wrought in England, the last week would be enough. None could doubt that the great multitude of his personal friends in the first half of his life, and the still greater multitude of those who have been instructed, consoled, and won to God by the unequalled beauty, the irresistible persuasion of his writings, at such a time as this, would pour out the love and gratitude of their hearts.

But that the public voice of England, political and religious, in all its diversities, should, for once, unite in love and veneration of a man who had broken through its sacred barriers and defied its religious prejudices, who could have believed it?

He had committed the unpardonable sin in England. He had rejected the whole Tudor Settlement in religion. He had become Catholic, as our fathers were; and yet, for no one in our memory has such a heartfelt and loving veneration been poured out. Some one (a non-Catholic writer) has said: ‘Whether Rome canonises him or not, he will be canonised in the thoughts of pious people of many creeds in England.’ This is true; but I will not therefore say that the mind of England is changed. Nevertheless, it must be said that, towards a man who has done so much to estrange it, the will of the English people was changed; the old malevolence had passed into good will.

If this is a noble testimony to a great Christian life, it is as noble a proof of the justice, equity, and uprightness of the English people. In venerating John Henry Newman it has unconsciously revealed and honoured itself.

In the history of this great life, and of all that it has done, we cannot forget that we owe to him, among other debts, one singular achievement. No one who does not intend to be laughed at, will henceforward say that the Catholic religion is fit only for weak intellects and unmanly brains. This superstition of pride is over. The author of the ‘Grammar of Assent’ may make them think twice before they so expose themselves. Again, the designer and editor of the ‘Library of the Fathers’ has planted himself on the undivided Church of the first six centuries; and he holds the field; the key of the position is lost.1

These are great words, pregnant of meaning. They will be remembered in connection with our two great Cardinals, so long as the “History of England” is read. For they mark the last half century of England’s history and of the history of religion, which is inseparable from that of the English people, in whom is so deeply rooted the natural religious instinct.

Every thinking man in England is either a believer or a non-believer in Christianity. Few profess to be indifferent on the matter. Few are disbelievers in Christianity; fewer still are Atheists. Every man, even if he is a non-believer, yet a man of some education and reflection, knows that Christianity has been the religion of all the most enlightened nations of the world for the greater part of twenty centuries, and of most of their greatest men, philosophers, statesmen, men of learning, and letters.

He knows that it began with the poor; at the first, “not many rich, not many noble, not many learned were called.” But gradually it spread among the learned and the noble, who were converted through beholding the lives of extraordinary virtue and heroism even to martyrdom, of poor working men and women; the modesty of Christian virgins, many of them, both men and women; their own slaves, as most of the working-class were in those ages of Imperial Rome. He knows that it was nothing but Christianity that created Christendom, where Heathendom had lain, infecting for ages all God’s fair earth, like the corrupting bones and corpses in Ezekiel’s vision.

It was Christianity that bid these corpses rise and live, that breathed into the dead world the Spirit from God, the spirit of charity and of liberty. For liberty is man’s conscious power of self-government, through aid of a new light and a new force, which was not in human nature before the coming of Christ. It was this new consciousness of the “perfect law of liberty,” of the liberty of the children of God, which gave to every Christian an intimate sense of right, and of duty to God and to all that God had made, and to “the powers that be, which are ordained by God.” It taught the right of every man to live and to possess the fruits of his toil; and in matters between his soul and God, to follow his own conscience, to be free from all human dictation in matter of religion. Such was the Charter of the Gospel, and such was the Christianity which was the creation of the Gospel, and which converted the world.

But there are some who admit all this, as historical fact, and yet say, we do not believe any longer in Christianity. If they are asked why, they will say, because Christianity, now, is not like Primitive Christianity. We could believe in that as a revelation from heaven. It proved itself by its fruits. It appealed to the people, to the working classes, to the masses of mankind. It was the very mark of Christ’s religion that “to the poor the Gospel was preached.” It endured three hundred years of martyrdom, yet it conquered the world; its strength was in weakness; it could not be human, it could not but have been divine.

So reasoned the men of the Oxford movement, when they began to put out the Tracts for the Times in 1833, and it was the spirit of John Henry Newman that inspired that whole movement.

These men of the Church of England believed firmly in Christianity as a divine revelation, and in Christ, as “God manifest in the Flesh” —“Emmanuel, God with us.” They studied the New Testament, and the Primitive Christian writers, who were the immediate disciples of the Apostles, and of their immediate successors; the writings of St. Ignatius, the disciple of St. John, of St. Irenræus his disciple, and St. Justin, the martyr. They went on to study SS. Cyprian, Cyril, Athanasius, Augustine, and the rest.

It was to this study that they were sent by the authoritative canons of the Church of England, as the best commentaries on Scripture, and the rule that the founders of the Anglican Church professed to have followed.

The men of the Oxford movement had thus formed for themselves what they believed to be the typical form of Primitive Christianity.

They turned then to compare it with the Christianity of the Church of England, and the more they contemplated the contrast, the more were they astounded and horrified at the prospect before them. They asked why was this. They did not stop at details, but went at once to the last reason of the thing.

They observed that the supreme characteristic of Primitive Christianity was an intense conviction that the Church was a divine power in the world: the visible kingdom of the God of heaven foretold by Daniel, gifted by its Divine Author with “the Spirit of truth,” of which Christ had said: “I will send to you the Spirit of truth, that He may guide you into all truth, and that He may abide with you forever;”2 and again, in our Lord’s last words ever spoken on earth, “All power is given to Me in heaven and upon earth; go ye therefore and teach all nations, baptising them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost, teaching them to observe all things I have commanded you, and, behold, I am with you all days, even to the end of the world.”3

They turned to St. Irenræus, the disciple of S. Polycarp, who was himself the disciple of S. John, and who wrote within fifty years of the Apostles. They found there, set forth, in the most luminous manner, that Primitive Christianity adhered to the teaching of a living body, already called the Catholic or universal Church, spread everywhere. Pagan writers like Tacitus, Suetonius, and Pliny have testified to this, as a fact known to all, within fifty years of the death of Christ. Of the Church, Irenræus speaks as a witness, from within, to the same fact, to which Pagan historians witnessed, from without.

“This preaching and this faith, once delivered to the Apostles by Christ, the Church having received, though she be spread throughout the whole world, carefully guards, as inhabiting one house, as having one soul, and the same heart, and delivers down as having one mouth. Nor have the Churches of Germany believed otherwise, nor of Spain, nor Gaul, nor in the East, nor in Egypt, nor in Syria, nor those of the middle of the world. But, as the sun, God’s creature, throughout the world, is one and the same; so, too, the preaching of the truth shines everywhere, and enlightens all men that are willing to come to the knowledge of the truth.”

“There being such proofs to look to, we ought not to seek elsewhere for the truth, which it is easy to receive from the Church, since the Apostles most fully committed unto this Church, as unto a rich storehouse, all which is of the truth. For this is the gate of life; all the rest are thieves and robbers. They must, therefore, be avoided; but whatever may be of the Church, we must love with the utmost diligence, and lay hold of the tradition of the truth.”

The teaching of S. Irenræus was seen to be one and the same with that of the earlier and later Fathers. I have selected his words, because they witness to the belief of the whole Church of the second century, of the Eastern portion of Christendom, of which Irenræus was a native, and of the Western portion also, for he was Bishop of Lyons in Gaul, when he wrote, and where he suffered martyrdom.

The men of the Oxford movement saw that Christians were no longer a united body, that the Protestant principle of the Bible, interpreted by each man’s private judgment, had utterly destroyed all unity of doctrine, and all idea of any divine authority residing in the Church and having the power and right to say what interpretations of Scripture were right, and what were wrong. Hence the endless multitude of Dissenting Sects in England, all offshoots from the Established Church.

They saw, too, that in the Church of England, the whole power of deciding what was to be taught in that Church, was vested in the Sovereign, by Act of Parliament, and depended in reality on the varying phases of public opinion, as represented by Parliament.

It seemed to them that the only thing to be done was to appeal to the Christian public opinion of the country, and to endeavour powerfully to act upon that. This decided them to put forward, in the “Tracts for the Times,” in the clearest manner, the contrast between Primitive Christianity, and the actual Christianity of the Church of England.

It was for the same reason that Newman projected and carried out the great work of translating the principal Fathers of the early centuries.

When Newman projected the “Library of the Fathers” he had certainly not the smallest suspicion that the movement would issue, through logical sequence, from premiss to conclusion, in his obligation in conscience to become, what he would then have called, a Roman Catholic.

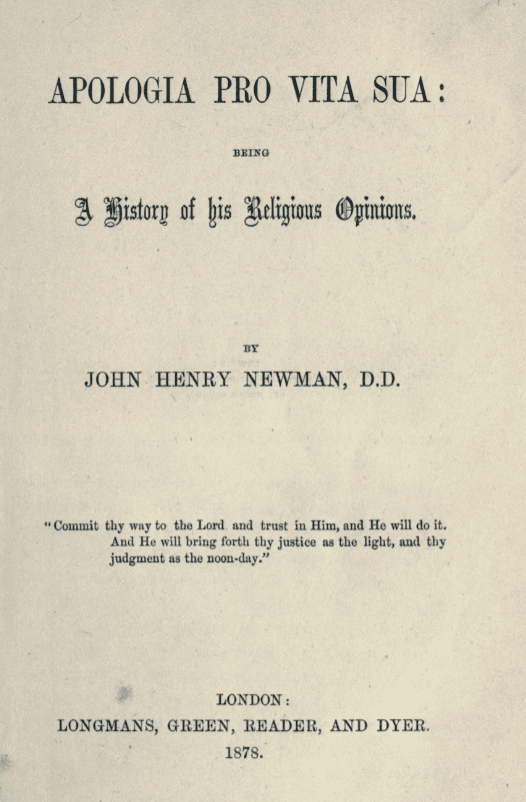

This comes out clearly in his “Apologia,” and in his “Anglican Difficulties,” and it is noteworthy, because Newman has often been accused of being a Papist in disguise. He tells us that, when he began the “Tracts for the Times,” in 1833, he believed that the Church of the Roman Communion was anti-Christian and idolatrous, in fact, that the Pope was the Anti-Christ of prophecy.

In the December of the year before, he had started with his friend Hurrell Froude, and others, on a tour in Italy, and spent some time in Rome. He received no religious impressions there. He says: “We kept out of the way of Catholics throughout our tour.” He went, in short, as most tourists go, with all the prejudices in which he had been brought up, and which he never doubted were a true and just view of things. He saw all things through this medium of prejudice, and came back as he had started. He says, speaking of his stay in Rome: “As to Church services, we attended the Tenebræ at the Sistine Chapel, but for the sake of the Miserere, that was all.” He went only to hear the famous music of the Papal choir, which, as a born musician, he was able fully to appreciate. He says: “My general feeling was, ‘All, save the spirit of man, is divine.’” He parted from his friends in Rome, and made a journey by himself through Sicily. There, he was taken dangerously ill with fever. His servant thought he would die, but he kept saying to himself: “I shall not die; I have a work to do in England. I shall not die, for I have not sinned against light.” In his illness in Sicily he was visited by the priest of the place, who had heard, probably from his Catholic servant, that an Englishman was dying, and would not send for a priest. Newman was too ill to talk. He says: “I felt inclined to enter into controversy with him.” But he had no thought of availing himself of his spiritual services. Referring to his Diary (June 1833) he says: “I was aching to get home. I felt I had a work to do. At Palermo I was kept three weeks waiting for a vessel. I began to visit the churches, and they calmed my impatience. I did not attend any service. I knew nothing of the presence of the Blessed Sacrament there. At last I got off in an orange-boat bound for Marseilles. We were becalmed in the Straits of Bonifacio. Then it was that I wrote the lines, ‘Lead kindly light, amid the encircling gloom.’”4

He arrived, at last, at Oxford about the second week of July. He writes: “On the following Sunday (July 14) Mr. Keble preached the ‘Assize Sermon’ in the University pulpit. It was published under the title of ‘National Apostacy.’ I have ever considered and kept that day as the start of the religious movement of 1833.”5

It was now that the work began, on which he had been ruminating during his journey and his illness, when he said: “I have a work to do in England. I shall not die; I have not sinned against the light.”

Lead kindly light, amid the encircling gloom

Lead thou me on.

I do not ask to see the distant scene,

One step enough for me.

“One step” was clear to him. It was to act, as we have said above, on Christian public opinion, and, if possible, bring back England to the truth, unity, and fervour of Primitive Christianity. The means he devised for this end was principally the “Tracts for the Times,” and the “Translations of the Early Fathers.” Another most important instrument was placed in his hands—the parochial pulpit of St. Mary’s University and parish church, of which he had been appointed Vicar. Newman’s beautiful series of historical sketches called the “Church of the Fathers” was published for the same end. He says: “The ‘Church of the Fathers’ is one of the earliest productions of the movement, and appeared, in numbers, in the British Magazine, being written with the aim of introducing the religious sentiments, views, and customs of the first ages of the Church into the modern Church of England.”6

The translation of Fleury’s “Church History” was also projected, and intended, to make English Churchmen familiar with the history of the early councils of the Church, of the controversies on which they pronounced definitive judgment, and by which the creeds used in the Anglican Church were framed; and developed, in order more fully to define the “faith once delivered” by the Apostles, and thus to meet each new attack of rationalizing heresy. Thus the work progressed from 1833 to 1841. Of this time, Newman writes: “So I went on for years up to 1841. It was, in a human point of view, the happiest time of my life. . . .We prospered and spread. . . .The Anglo-Catholic party (as it is called) suddenly became a power in the National Church, and an object of alarm to her rulers and friends. . . . It seemed as if those doctrines were in the air, and that the movement was the birth of a crisis rather than of a place or party. In a very few years, a school of opinion had been formed, fixed in its principles, indefinitive and progressive in their range; and it extended itself into every part of the country. Nay, the movement and its party-names (Puseyite, Newmanite, Tractarian), were known to the police of Italy, and to the backwoodmen of America. . . .And so it proceeded, getting stronger and stronger every year, till it came into collision with the nation and the Church of the nation; which it began by professing, especially, to serve.”7

The “Tracts for the Times” and the “Library of the Fathers” obtained a wide circulation, and formed a school in the Church of England. They may be said to have, in a sense, created the present Church of England. For very few Churchmen would now deny that Christianity is essentially connected with a visible Church, which, at least in General Council, would be infallible. The claim of every Churchman is, that the Church of England is a part of the Catholic Church of the days of SS. Irenæus, Cyprian, and Cyril, and the rest.

They avoid thinking of their separation from the rest of Christendom, under the “Tudor settlement” of the Church of England, by law established and by authority of Parliament, as a National Church. They have no theory of the Visible Unity of the Church, which fits in with the visible fact of disunion, and they take refuge in words which, if they mean anything, have reference only to the invisible Church, which Catholics also admit, but in which they would charitably include every soul that is right with God, dissenters of all shades, and possibly even some Pagans, according to the teaching of the great Jesuit theologians, such as De Lugo, Suarez, and others.

But to return to our narrative. Several important public events brought out more and more clearly, in the minds of Newman and of those who acted with him, the absolute Erastianism, or complete dependence on the State, of the Church of England. The Whigs were in office; Liberalism in religion was in the ascendant. The appointment of Dr. Hampden, one of the leading clergy of the Liberal or Broad Church school, suspected of Arian or Socinian leanings, to a bishopric, against the vehement protest of the University of Oxford and of many of the bishops, showed this complete servitude to the State, and to the Prime Minister of the day, who happened to have a majority in the House of Commons.

Then came a project of the Government, to which the bishops assented, to establish, in concert with Prussia, an Anglican bishop at Jerusalem, who was to rule over Lutherans, Calvinists, and Anglicans, and to hold communion, if they saw their way, with Nestorians, and Eutychians—heretics condemned by the General Councils, by which the Anglican Church, in her canons, professed to be bound. An Act of Parliament was passed to enable the Archbishop of Canterbury, by royal authority, to consecrate this bishop. The Archbishop consented, saying, as he had said in the case of Dr. Hampden, that he had no authority against an Act of Parliament and the royal supremacy over the Church.

This had the effect, as it were, of a revelation on the men of the Oxford movement. They began to see more clearly that the Church of England was, by its very constitution, simply a department of the State, and they saw moreover that this condition of things in the Church of England had continued all along, ever since the false step taken in the sixteenth century, when the English sovereign, with the full consent of the bishops, and by Act of Parliament, made himself head of the Church, and through his Law Courts, “in all causes ecclesiastical as well as civil, Supreme.” A few years later, after Newman had left the Church of England, this same servitude of the Established Church to the State was brought out, even more clearly, in the decision of the Law Courts, in the Gorham case, by which the doctrine of regeneration in baptism was made an open question in the Church of England. It was this revelation of the Royal Supremacy in matters of doctrine and discipline that led to Newman’s secession, and to that of his immediate disciples. It was the revelation, in the Gorham case, that was the immediate cause that led to the submission to the Church of Archdeacon Manning, and of those who, like the Wilberforces, Hope Scott, and a host of others, became Catholics about the same time as our Cardinal Archbishop. It was he who, at that time, said: “The Gorham case is a revelation to us; it has opened our eyes to the false step made by the Church of England under the Tudor settlement.” When some were deliberating what to do, whether to submit to the Pope, or to form a Free Church of England, independent of the State, it was Manning who spoke memorable words. “No,” said he, “three hundred years ago we left a good ship for a boat; I am not going to leave a boat for a tub.”

However, in 1841, the leaders of the movement had not got so far as to think of leaving the Church of England. They still hoped. Newman writes:

“I thought that the Anglican Church was tyrannised over by a mere party.” Their hope was that they might be able gradually to influence the Christian public opinion of the country, and draw it to a desire of returning to Primitive Christianity and the Church of the Fathers. They did not then see that the Catholic Church is the Visible Kingdom of God upon earth, essentially one, and visibly united in its Head, the Bishop of Rome, successor to St. Peter, whom Christ had made the centre of unity, and placed on that “chair of truth,” against which He had declared “the gates of hell should not prevail against it.”

Newman, eminently, and for long years; had made the history of the early centuries of Christianity the matter of his pro found study. We, his disciples (for I came under the influence of his mind about 1839 or 1840) were directed by his writings into the same line of study. We knew that the Fathers, St. Athanasius, St. Leo, and the rest, whom we took as trustworthy witnesses of the faith of the Primitive Church, were the chief agents in preserving the Church from Arian, Nestorian, Eutychian, and other errors, especially by means of the General Councils, which expressed the infallible authority of the Church; and we say that if it had not been for the perpetual indwelling of the Holy Spirit in the Church, it would have been impossible for the faith to have been preserved, amidst the revolts of rationalising Christians, Alexandrian Platonists, and Jews and hair-splitting Greek Sophists.

But we saw no less clearly that the Church of England had become little more than a department of the State, and that it had helplessly abdicated all claim to an independent judgment in all matters of religious faith.

We perceived also, gradually, and were helped to see it, through Newman’s supereminent knowledge of ecclesiastical history, that the Bishop of Rome had always been the supreme agent in keeping the whole Church united; in the Councils, also, he always had held the most prominent place, as well by his legates who presided, as by his sanction of their decrees; which were considered binding on the whole Church, only when they had received his approval.

Moreover, the more we read these early Christian writers, the more clearly did we see that, besides the doctrines which the Church of England held in common with Rome, nearly every doctrine which the English Reformation had rejected, was held to be part and parcel of the Christian faith by those authorities of early Christianity—I mean such doctrines as the Real Presence and Sacrifice of the Mass, so clearly taught by St. Clement of Rome, who speaks of the “Eucharistic Offering to God,” which has succeeded to the oblations at the altar in the Old Law. St. Ignatius, of Antioch, again says, speaking of certain heretics, “They abstain from the Eucharist and the Oblations, because they do not confess that the Eucharist is Flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, the Flesh which suffered for our sins, which the Father in His mercy raised again,” &c. St. Justin, the martyr, and St. Irenæus, are equally explicit. Well do I remember the first time when, at Oxford, I read these and many similar testimonies, in the “Library of the Fathers,” especially a long passage in the “Catechetical Instructions” of St. Cyril of Jerusalem, in which he says that the bread and wine are changed into the Body and Blood of Christ, as truly as the water was changed into wine at the marriage of Cana in Galilee.

In short, we became convinced that, on these doctrines, as also on those of purgatory, prayers for the dead, the honour due to the Blessed Virgin and the Saints, and our right to ask their prayers, and last but not least, on the authority of the Pope; or as St. Irenæus calls it, “the superior Headship of the Church, founded at Rome by SS. Peter and Paul, to which Church all Churches and all the faithful in the whole world were bound to have recourse, or to be united with it in communion,” the ancient Church and the Church of the Roman communion were substantially agreed.

These studies had led many of us to think seriously, that it might be our duty at once to make our submission to the Catholic Church, which we saw had its centre at Rome, and, as it would seem, was by divine institution, head of the visible Church.

Newman was not as yet convinced that the Roman supremacy over all Churches was a matter of divine institution. He thought it was in the mind of our Lord, in His words to Peter, as the normal condition of the Church; but he then supposed it was only indirectly of divine, but was directly of ecclesiastical institution. It was only in 1844, when he had reviewed all his studies, throughout more than fifteen years, of the Fathers and the Councils, and of the whole course of ecclesiastical history, that in the course of writing his “Essay on Development,” he came to the conclusion that the supremacy of the Pope was the key-stone of the arch, and that it was his own indispensable duty in conscience, to submit himself to the Roman obedience.

Thus, as I have shown, a fundamental revolution had been taking place in our idea of the Church, and of Christianity. For the first time, the vision of the world-wide Church, in its majestic unity, had come before us. We saw it, for the first time, not as we had supposed it to be, an aggregate of congregations—a voluntary union of spiritual families, but as a world-wide essentially united kingdom—the Kingdom as shown to the Prophet Daniel, like to a stone cut from a mountain without hand, set up by the God of heaven, which was to be gradually developed until it became a mountain filling the whole earth, destined to last for ever. Of this world-wide Church, we know the Church of England was once a portion. How it could form any part of that unity, since its separation 300 years before, we could not see.

From the moment that we were convinced that the charges against the Roman communion, of being idolatrous, anti-Christian, and the rest, had been answered, they were completely banished from our minds. The fact that it formed the vast majority of Catholic Christendom, necessarily took away the chief ground of our Protestant position. Sides were changed; we saw that we had to defend our protest, or else yield to the authority we had protested against.

But Newman and others of our leaders had not, as yet, come to this point. They thought Rome was right in claiming the headship of the Church; but they also considered that a legitimate claim may be pushed too far. They reflected that there had been abuses in the Papal relations with England, in old times, demands for large money payments, and for the grant of the incomes of English Bishoprics and other rich benefices, in favour of Italian ecclesiastics, which had been a grievance in old times, against which English Catholic sovereigns had uniformly protested.

These, and other things had led, first to a coolness on the part of the English towards Rome, in Catholic times, and this had grown up, especially, during the days of the anti-popes, when rival Pontiffs each claimed the obedience of Catholics, and the justice of the claim of each was so open to doubt, that England embraced the obedience of one Pope, France and Scotland of another, and Spain at one time owned the authority of a third claimant. In fact, the contention between the popes and anti-popes was, to a great extent, a battle of rival nationalities.

Such historical difficulties, and many others, helped to complicate the question, and the result was that the most of us resolved to stay by Newman; doubting the soundness of our own conclusions to which, with far greater knowledge, he had not arrived.

Three of us younger men, however, went off, and were received into the Catholic Church; and it is somewhat singular that these three men were Scotsmen, Johnstone Grant, of St. John’s College, now a Jesuit; Edward Douglas, of Christ Church, now a Redemptorist; and his friend Scott-Murray, squire of Danesfield, deceased. I was soon to be another Scotsman added to the list. I suppose our coming from Jacobite and Scotch Episcopalian stocks, and not being so rooted as Englishmen are, in favour of everything English, left us freer to criticise and condemn Church of England Christianity.

Our secession was decided by several things: The publication by Newman of Tract 90, the object of which was to show that there was no need to go to Rome, because we found nearly all Roman doctrines were taught in the Primitive Church, although rejected or neglected by the Church of England; because the 39 Articles were not articles of faith, but an attempt at compromise. They were intended to include Puritans, and Catholics who were ready to give up the Pope. This confirmed our growing convictions—our disgust with the Church of England was all but complete, and it only increased this disgust, if it could be shown that her founders had deliberately ventured to obscure the old religion, by what Newman had called “the stammering words of ambiguous formularies.”

The Tract made a great stir throughout the University and the country; but, as every one knows, the interpretation of the Articles was furiously repudiated by the Anglican bishops, and by the Protestant public-opinion of the country. The bigotry and intolerance of the Puritan party was stirred to a white heat. Newman saw that his attempt to find terms of reconciliation, and to speak of the creed of Rome, as substantially identical, differing only on minor points, from Primitive Christianity, with which the Anglican Church professed to agree—had failed. But the truth has proclaimed itself trumpet-tongued throughout the English-speaking world.

It has in our day come to be admitted by all. It is now, I think, twenty years, since I copied the following passage from the Saturday Review, no friend, as we know, to Catholics, nor to the Catholicising movement in the Church of England: “The distinctive principle of the English Reformation was an appeal to Christian antiquity, as admirable, and probably as imaginary, as the ‘Golden Age’ of the poets. The era of the Protestant Reformation was before the age of accurate historical criticism. The true method of historical criticism was as yet uncreated, and it is not too much to say, that, whatever accurate knowledge we now possess of the Church of the first centuries, has been obtained within the last fifty years, and that a better acquaintance with the remains of antiquity has convinced us that many doctrines and practices, which have been commonly accounted to be peculiarities of later Romanism, existed in the best and purest ages of Christianity.”

No one could ignore Newman’s part in this remarkable change in public opinion, and in the historical judgment of educated men of whatever creed, or of no creed at all. It is this which Cardinal Manning expresses, when he says: “The designer and editor of the ‘Library of the Fathers,’ has planted himself on the undivided Church of the first six centuries of Christianity; and he holds the field. The key of the position is lost.” The old Anglican claim to hold a via media on the basis of Christian antiquity, between Catholic Christendom on the one side, and Protestantism on the other, has been for ever exploded.

The second thing which hastened my submission to the Catholic Church was the reading of a Catholic book, Milner’s “End of Controversy.” Some years before I had taken the book away from my friend Johnstone Grant, to whom it had been given by a Catholic priest in London. I rated him soundly for reading a Catholic book, told him he had no more right to read it, than to study a Socinian or Infidel book. The book lay in my drawer in college.

Newman’s sermons and Pusey’s writings, on baptismal grace and post-baptismal sin, had wrought in me a moral revolution, and a terrible fear that I had lost God for ever. I saw myself a baptised Christian and, therefore, once a temple of God. But through the sins of childhood and of thoughtless youth, reduced to a state in which I could not doubt that I had lost the grace of God, and my soul had become a dwelling-place of devils. Anglican theology taught clearly, in its Prayer Book and Catechism, almost as clearly as it is taught in the Catholic Catechism, that souls are regenerated in Baptism. But it tells of no other Sacrament by which sins committed after Baptism may be remitted. At that day, no one thought of proving the belief of the Church of England in the Sacrament of Penance, Confession, and Priestly Absolution, from the few words about the absolving power in the Anglican ordination service, and in that for the visitation of the sick. Any one who wishes to do so, may find the doctrine there. I had never heard of it, until, in an hour of deep mental distress, I turned over the pages of Milner’s End of Controversy. There I first heard of the Sacrament of reconciliation after post-baptismal sin, and it was Milner that sent me to the Anglican Prayer Book, for proof that the Church of England admitted, in theory, the same doctrine on this point, as had always and everywhere been, not only taught, but practised in the Catholic Church.

This discovery was a great relief to my mind, but it did not increase my confidence in the Church of England. There were the “stammering words of ambiguous formularies” once more. What was to be said of a Church which had so obscured a divine ordinance for the remission of sin—a Sacrament therefore, by its own definition; to quote the words of the Catechism: “A Sacrament is an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace given to us; ordained by Christ Himself, as a means whereby we receive the same, and a pledge to assure us thereof.”

Here then was a Sacrament, so necessary for salvation, which had practically fallen into complete disuse in the Church of England for 300 years!

It was difficult to try Confession in the Anglican Church. However, I made the attempt, as at least a moral discipline. Archdeacon Manning, whom I knew, was in Oxford, for it was his turn to preach the University sermon. I went to Confession to him in Merton College Chapel, his own college. It was a relief to me for a time. He also gave me excellent advice, and, I think, counselled me to put myself under Newman, and try to remain and take Orders in the Anglican Church. I tried to do so. I was admitted, by Newman’s great kindness, as one of his first companions at Littlemore. I remained with him about a year. The life was something like what we had read of in the “Lives of the Fathers of the Desert” —of prayer, fasting, and study. We rose at midnight to recite the Nocturnal office of the Roman Breviary. I remember, direct invocation of Saints was omitted, and, instead, we asked God that the Saint of the day might pray for us. I think we passed an hour in private prayer, and, for the first time, I learned what meditation meant. We fasted every day till twelve, and in Lent and Advent till five. There was some mitigation on Sundays and the greater festivals. We went to Communion at the village church and to the service there, morning and evening, every day; we went to Confession every week. Once after Confession I said to Newman, “Are you sure you have the power of giving absolution?” He paused, and then said in a tone of deep distress, “Why will you ask me? Ask Pusey.” This was, I think, in the spring of 1843. It was the first indication I had received that Newman had begun seriously to doubt his position in the Anglican Church. I see from his “Apologia” that his doubts, as to whether the Church of Rome was not altogether in the right, and the Church of England wholly in the wrong, had taken root in his mind about that time.

I had promised him, soon after going to Littlemore, that I would stay three years. He had made it a condition. I gave the promise, but after a year l found it impossible to keep it. With great grief I left my dear master, and made my submission to the Catholic Church. My secession led to Newman’s resigning his parish. His last sermon, as an Anglican, was preached at Littlemore. It is entitled “The Parting of Friends.” He thought he was compromised by my act, and he was much displeased with me for breaking my promise.

After two years, he and his other companions at Littlemore were received into the Church.

We left the Church of England with grief. All the good we knew, we had learned there; we had been led step by step by God’s grace, but we left, because we could not close our eyes to the fact that the Church of England was no part of a Visible Church; rather than separate from which Sir Thomas More, Bishop Fisher, and hundreds of others have laid down their lives in martyrdom.

Almost the first thing Newman did after his reception into the Church was to take the trouble to come all the way to Ratcliffe College, in Leicestershire, where I was studying, to see me, in order to show that he blamed me no longer. A year after I was ordained priest I went to see him, when he was living in community with Father Faber, Dalgairns and others at St. Wilfrid’s in Staffordshire. They had all been ordained. I remember he would serve my Mass, as an act of humility and affection. Since that time I have always paid him an annual visit at the Oratory, Birmingham, where he always received me with the most cordial affection. When I first went to Rome, as representative there of my Order, that of the Fathers of Charity, founded by Rosmini, he gave me, as Cardinal, a letter to the Pope. This introduction has been, for the last eight years, of immense service to me in Rome.

Soon after Easter of this year I paid him my last visit. He sent for me to come to him, before he rose in the morning, saying that after dressing, he might feel himself too much exhausted to receive me. I found him weak, weak indeed, in body, but as bright and clear in mind as ever. I told him news from Rome which I knew would interest him. He listened with all his old intensity of thought; fully appreciated the facts and the situation of matters ecclesiastical and political.

I knelt down; took his hand, and kissed it. I felt sure I should not see him again. I thanked him for all the good he had done me, since, under God, he had been, as I hoped, the instrument of my salvation. I asked his blessing, which he gave me with great earnestness, simplicity, and tenderness. Three months later I stood by his bier.

O, great and holy soul, remember us with God, and may our prayers and masses avail to thine eternal rest and peace.

WILLIAM LOCKHART, B.A. Oxon.

1 Cardinal Manning’s entire oration is published in print and can be read in the NINS Digital Collections. Edmund Sheridan Purcell, Life of Cardinal Manning: Archbishop of Westminster (Macmillan and Co., 1896), 2:749–52.

2 John 14:16–17.

3 Matthew 28:18–20.

4 Newman, Apo (Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1864): 99.

Share

Angela Baker

Angela Baker was an intern at the National Institute for Newman Studies (NINS) during the summer of 2024, and now serves as the Digital Humanities and Editorial Specialist at NINS.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS