Charles Warren Adams: A Victorian Society Scandal

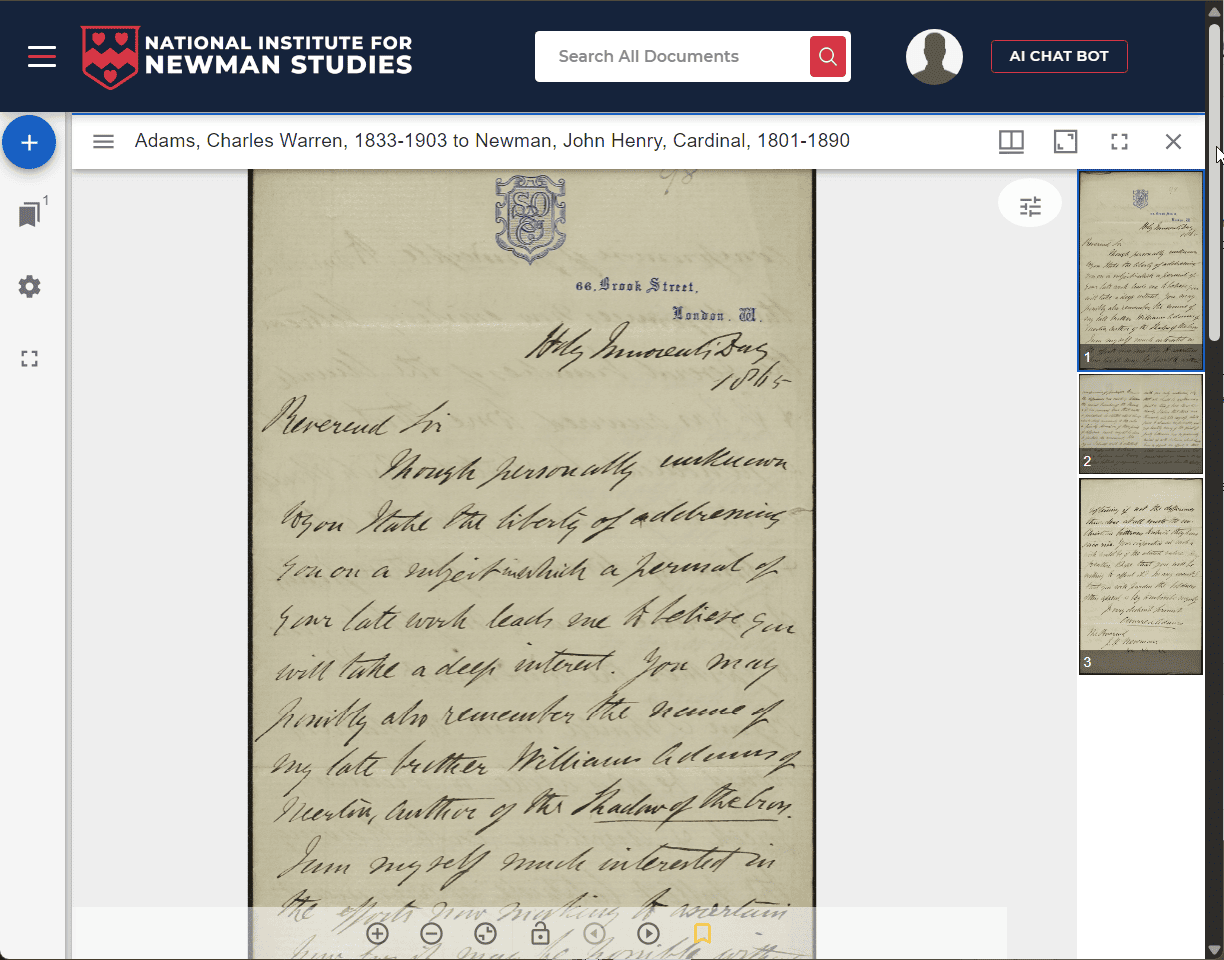

There are two letters from Charles Warren Adams included in the NINS Digital Collections, the first is dated 1862 and is addressed to Bishop Grant of Southwark. This letter expresses Adams’s concerns about his brother’s drift towards Catholicism. The second letter is dated 1865, is addressed to Dr. Newman, and discusses matters of theology.

Adams (1833–1903) was a London journalist, who was an author in his spare time. Under the pseudonym Charles Felix, Adams wrote the detective novel The Notting Hill Mystery (1865), which is widely acknowledged as one of the earliest examples of detective fiction. The detective in the story, Ralph Henderson, was said to have inspired the creation of characters such as Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot.1 His mother, Charlotte Adams, was also a noted author. He invested in the notable publishing firm of Saunders, Otley & Co, which he attempted to rescue when the other partners died, though he was unsuccessful in preventing its liquidation in 1869, causing his own financial ruin. In April 1860 it was reported in the newspapers that Charles was caught up in the religious riots at St. George’s in the East over his support of the Rev. Bryan King in his attempts to introduce more Anglo-Catholic ritual into the services.

Charles Adams’s lineage is a noble one. His family seat was Ansty Hall in Warwickshire, which the Adams family had held since Jacobean times. However, Charles was the younger son of a younger son, and since the death of his grandfather, Simon Adams, the estates were passed down the senior line of the family. The estates were passed down the senior line of the family and were at the time of the scandal held by his first cousin, Captain George Curtis Adams, RN, then on his death in 1883 passed to his son, Henry Cadwaller Adams. Charles’s father was a prominent lawyer who rose to become Serjeant at Law.

Charles Adams first married in October 1861 to Georgina Alethe Polson, who died in 1880. They had one child—a daughter named Charlotte, who never married and who died in 1958 at St. Mary’s Convent, Chiswick.

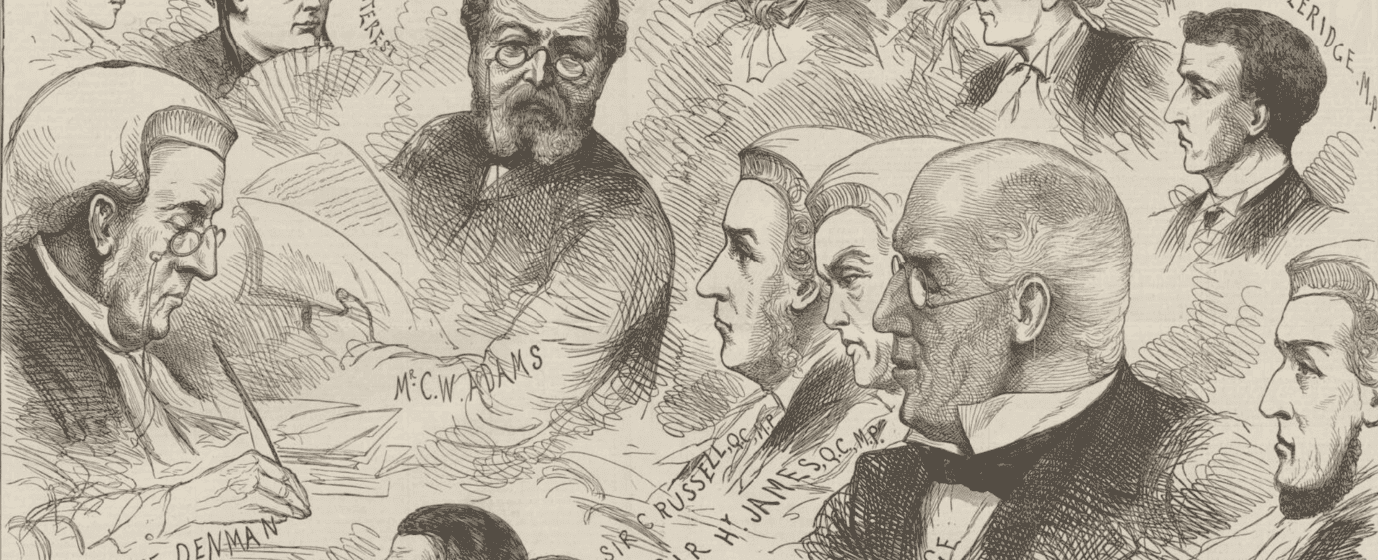

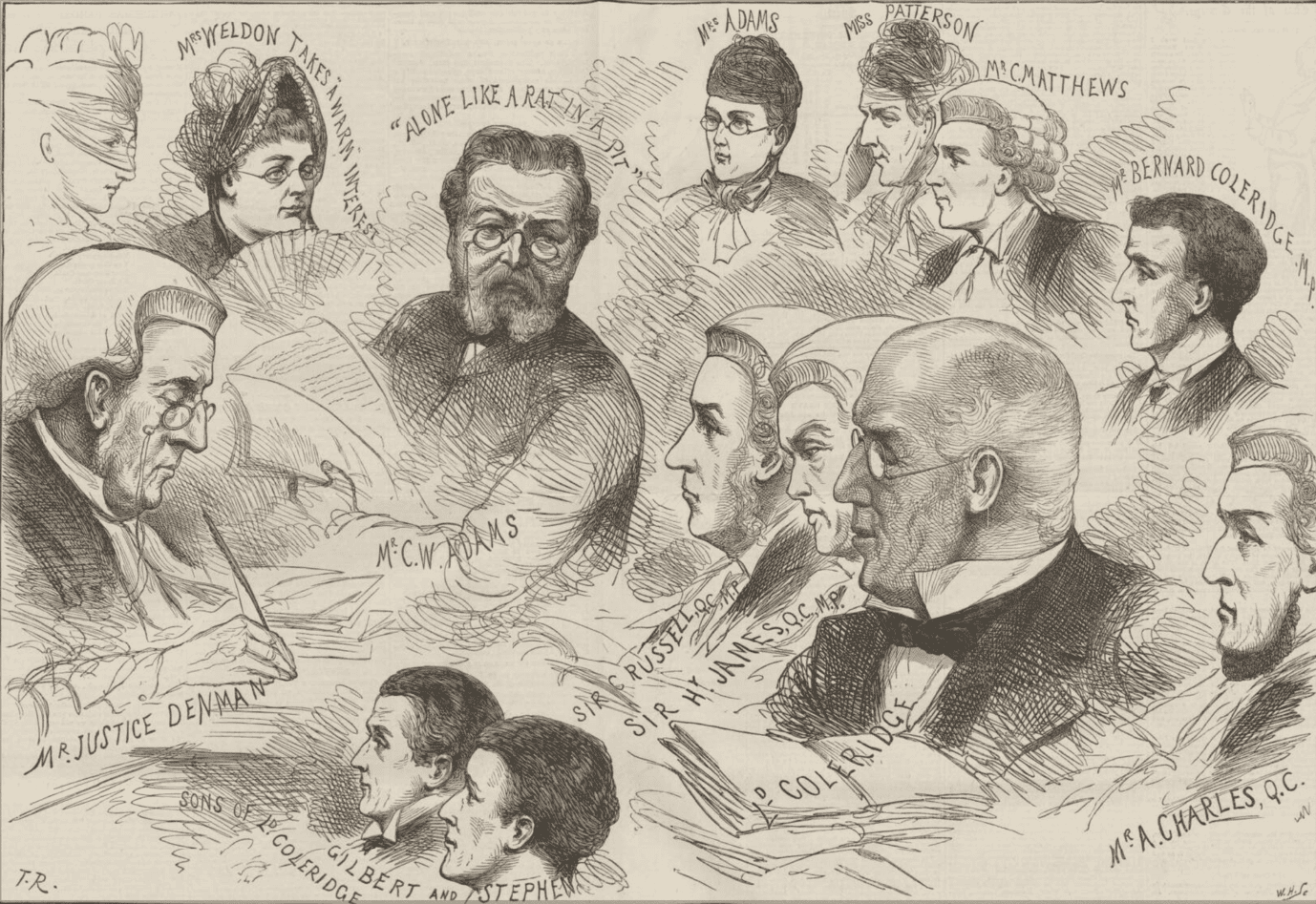

Following Georgina’s death, Charles became involved in a major society controversy over his relationship with the 33-year-old Mildred Mary Coleridge, who was the daughter of Newman’s old friend Baron Coleridge, the Lord Chief Justice. Newman had known Mildred since she was a small child. Baron Coleridge’s brother was Father Henry James Coleridge, SJ., an Oxford Movement Convert, who was by this time a prominent member of the Jesuit community at Farm Street, London. He was also a regular correspondent of Newman’s.

The scandal developed through the Victoria Street Society (the Anti-Vivisection society), where Adams was employed as the administrator and secretary in January 1881. The anti-vivisection cause attracted many key figures of society, including Baron Coleridge himself and even Cardinal Manning. Mildred had joined the Victoria Street Society in 1878, then after his employment, Adams had encouraged her to take a more active role in matters of administration. The two soon became friends, but, on 3 November 1882, the Society chair, Miss Cobbe, leveled allegations of impropriety against Charles, accusing him of compromising Mildred.

Charles and Mildred both denied any wrongdoing, and in protest, Mildred resigned from the Society. Charles was then sacked from his job. Baron Coleridge attempted to ban his daughter from associating any more with him, but she defied this ban, and they continued meeting.

At the age of 35, with Mildred generally accepted to be past marriageable age, the widowed Baron Coleridge expected her to devote her life to caring for him and her brothers. Even though both Mildred and Adams continued to insist that there was no romantic relationship between them, that they were merely friends, the Coleridge family continued to try and prevent them from meeting.

In May 1883, Coleridge summoned Adams to his study for a private meeting. There Adams declared that although “he was not in love with” Mildred, if the family harassment of their friendship continued, they would however become engaged, which they did in June 1883, to the continuing objection of Lord Coleridge, who stated that he believed Adams to be a “blackguard and fortune hunter.”2

To escape a hostile environment with her family, Mildred left home and took lodgings. Her brother, the Hon. Bernard Coleridge, wrote a letter attacking Adams who then sued him for libel. The case ended in November 1884 with the jury finding for the plaintiff and determining the damages at £3,000. The judge, however, set aside the jury’s decision, declaring that the letter was a privileged communication. In November 1886, Adams again attempted to recover these damages, but this time the court ruled for the defendants.3

A book has been written about the case, entitled, Shattered Idol: The Lord Chief Justice and His Troublesome Women.

Ultimately, Charles and Mildred married in June 1885, at which time her family disowned her entirely. The newspapers reported that “The wedding was strictly private, Lord Coleridge having refused his daughter’s request to be present, no invitations were issued to the Coleridge family.”4 Mildred’s mother’s family did however attend, and the officiating priest was her maternal uncle the Rev. H. F. Seymour. Despite this, Baron Coleridge did agree to settle an allowance on his daughter, but they never spoke again.

After their wedding, the couple traveled within Europe for many years. Following the death of Baron Coleridge in 1894, they returned to live quietly in Milford-on-Sea, a village on the south coast, where they purchased a large house called Harewood. In the 1901 census, they had a small household of four servants: a cook, parlor maid, house maid, and a sick nurse. The sick nurse was presumably caring for Charles who had heart failure and who died in 1903 at the age of 69. Mildred remained at Harewood. In the 1911 census the house was described as having twenty rooms, and she employed a housekeeper, parlor maid, and a between-maid. By 1921, when she was aged 73, her domestic household had been reduced even further, and she employed only a single maid. She died there in 1929, leaving Harewood to Charles’s niece, having not spoken to any member of the Coleridge family since the 1880s.

Within Newman’s letters with the Coleridges, there is little mention of the scandal. However, in a letter dated November 1884, Baron Coleridge thanked Newman for his kindness and support, which presumably relates to this matter.

You can read Adams' letters and other correspondence in the NINS Digital Collections, with links below:

Letters from Charles Warren Adams

Letters from Mildred Coleridge (later Adams)

Letters from Father Coleridge, SJ

1 Paul Collins, “Before Hercule or Sherlock, There Was Ralph,” The New York Times Book Review (7 January 2011).

2 David Pickup, “Old Maids and Fortune-Hunters,” The law Society Gazette (5 August 2025).

3 Portsmouth Times & Naval Gazette (27 November 1886): 5.

4 Edinburgh Evening News (24 June 1885): 3.

Share

Lawrence Gregory

Lawrence Gregory is the NINS senior archivist and UK agent, and a historian of nineteenth-century English Catholicism, who also enjoys cats and steam trains.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS