A Window into the Rambler Controversy

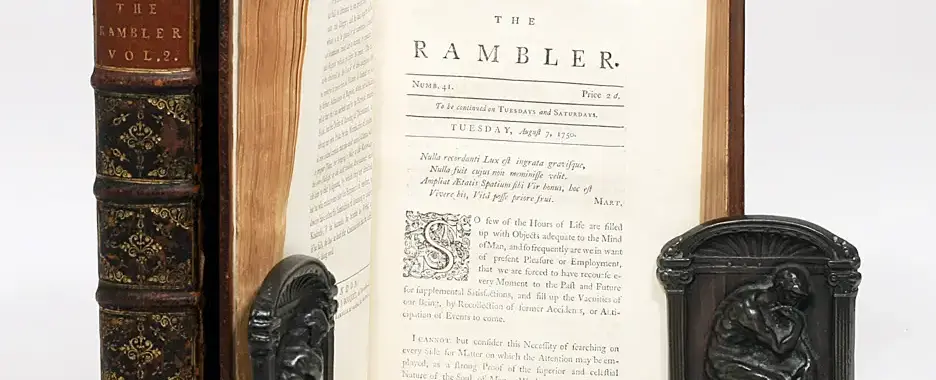

One of the most exciting aspects of an extensive archive like the National Institute for Newman Studies Digital Collections is the chance to peek into the day-to-day lives of the historical figures we so often read about in drier academic texts. During my internship for NINS, I took great pleasure in reading the letters of Richard Simpson, a former Anglican priest numbered among the prominent Catholic converts of the time. He was most known for his involvement in the Liberal Catholic movement through the Rambler, a periodical which served to allow the prominent lay converts of the time to express their views to the masses. We currently have a total of 64 letters penned by Richard Simpson in the Digital Collections, of which most were directed to St. John Henry Newman. Despite their often-mundane nature (as is often the case with historical letters), they provide a window into the man Richard Simpson, as well as into the unfolding of the Rambler situation in 1859 as it suffered attacks by the English Bishops.

In a time when the principle that “the terms ‘lay’ and ‘theologian’ were incompatible” still reigned supreme, a project like the Rambler was quite divisive.1 Richard Simpson, for his part, was particularly adept at summoning controversy to himself. In a time when the English Church was so divided, he found his way into all sorts of hot water. Simpson was an extraordinarily talented writer who covered a wide variety of subjects: theology, philosophy, and literature, just to name a few. He was a great admirer of Newman, and between the two there was strong mutual respect. He also had a fiery temper, which was reflected in his “pugnacious, impish, and unconsciously flippant literary style,” which won him many enemies as he covered his often-theological topics with no regard for the scandal it could and did cause.2 Although he had many well-documented run-ins with the episcopacy regarding his writings in the Rambler, the Digital Collections have the most of Simpson’s letters from the aforementioned 1859 dispute over the editorship of the Rambler.

A year earlier, in 1858, a Royal Commission was set to investigate the state of English education.3 This Commission had no Catholic member, but nonetheless had the task of examining Catholic schools, in addition to the rest. Because of this lack of a Catholic member, the Church refused to allow the inspectors into the schools or to cooperate with them. This threatened state grants to the schools. On this matter, articles were published in the Rambler urging the Church to cooperate with the Commission. The Bishops, however, being placed in such a precarious position between the possible loss of funds and undue cooperation with the English state, attempted to shut down the conversation, in part justifying that education is a sufficiently theological topic to be unsuitable for laity to discuss. Simpson, now the editor of the Rambler, refused and allowed further publications, igniting the full ire of the episcopacy against him.

On 12 February 1859 the Bishops, most notably Cardinal Wiseman and Bishop Ullathorne, met and came to the decision that the Rambler needed to be removed from Simpson’s control. The task of pulling Simpson away from the Rambler fell to Newman, for whom Simpson had undying adoration and whose requests could not be refused by Simpson. Newman summoned Simpson, who was already in a tough spot. In a letter dated 17 February, Simpson noted that Newman’s summons came when he was caring for his mentally ill brother, and when John Acton, Simpson’s close friend and collaborator, had left for Europe and left everything in Simpson’s lap. Now the Bishops demanded the suppression of the already-printed March 1859 Rambler and his resignation all at once! Simpson was able to make it to Birmingham the next day with difficulty, and in their meeting, it was apparent that Newman was the only viable replacement as editor.

Simpson’s great respect for Newman, thanking him for his consideration for the Rambler, was contrasted with his disdain for the Bishops, in which he referred to their intentions as “tyrannical and despotic,” and set himself as Naboth having his vineyard stolen by Ahab. Just a few days later (though not, as he admits in the same letter, before airing his fury to his circle of friends), he retracted his terse words about the bishops, saying to Newman that he wished “to retract all the passionate things I have said about our Bishops,” and expressed his aspirations that a rival magazine, the Dublin Review, be immediately destroyed, lest his pugnacity and impishness should be forgotten. While Newman certainly agreed with Simpson in some ways—i.e., that the Rambler was a burden that Newman did not want to have—as he delayed his decision over the course of the month of March, Simpson’s feeling both of dismay at the bishops and impatience for closure on the matter grew steadily, as is evidenced in the significant number of letters exchanged between the two. He contended with the veiled jabs made at the Rambler by the bishops, kept up a steady stream of answers to Newman’s various reasons against taking up the office, and spoke of “calamity” and the like more than once.

Finally, the good news came on 22 March that Newman had accepted the editorship the day before, giving Simpson hope that the whole matter would be somewhat at rest. A flurry of activity can be found in the many letters in the following weeks as he organized the Rambler’s affairs. Newman, despite the hopes of the bishops, maintained the magazine’s political leaning.4 Two months later, on 25 May, Simpson’s hopes would be dashed yet again, with Newman too being forced to resign the Rambler. Simpson immediately resumed his complaints of persecution. However, in this case, John Acton was able to take over in shorter time, despite him being one of the liberals whom the bishops wished to keep away from the Rambler.5 Although the Rambler’s troubles did not end here (it met its final end just a few short years later), this particularly turbulent chapter in its history gave way in the course of just a few months of 1859.

Conclusion

This short article demonstrates just how valuable first-hand accounts of these controversies are, especially when they are in the form of letters made in confidence between people who are close with each other, as Simpson was with Newman and a number of others like Acton (although I have not explicitly made reference to Simpson’s letters to the latter). The core of the struggle for Simpson, which is apparent in his letters, is his gift for all manner of study, both theological and otherwise. It is a reminder of the differences between our present day and the past when we read first-hand the level of control exercised by bishops and the level of censorship, which would be unheard of today. Although he would also make a name for himself in literary studies, the height of Richard Simpson’s notoriety was during the Rambler controversy, just as much a part of his public life.

1 Damien McElrath, “Richard Simpson and John Henry Newman: The Rambler, Laymen, and Theology,” Catholic Historical Review 52, no. 4 (January 1967): 533.

2 McElrath, “Richard Simpson and John Henry Newman,” 510.

3 Josef Lewis Altholz, The Liberal Catholic Movement in England: The “Rambler” and Its Contributors, 1848–1864 (Hassell Street Press, 2021), 88.

4 Altholz, The Liberal Catholic Movement in England, 103.

5 Altholz, The Liberal Catholic Movement in England, 93.

Share

Miles Bertrand

Miles Bertrand is an undergraduate student of Mathematics, Philosophy, and Catholic Studies at Duquesne University.

Topics

Newsletter

QUICK LINKS